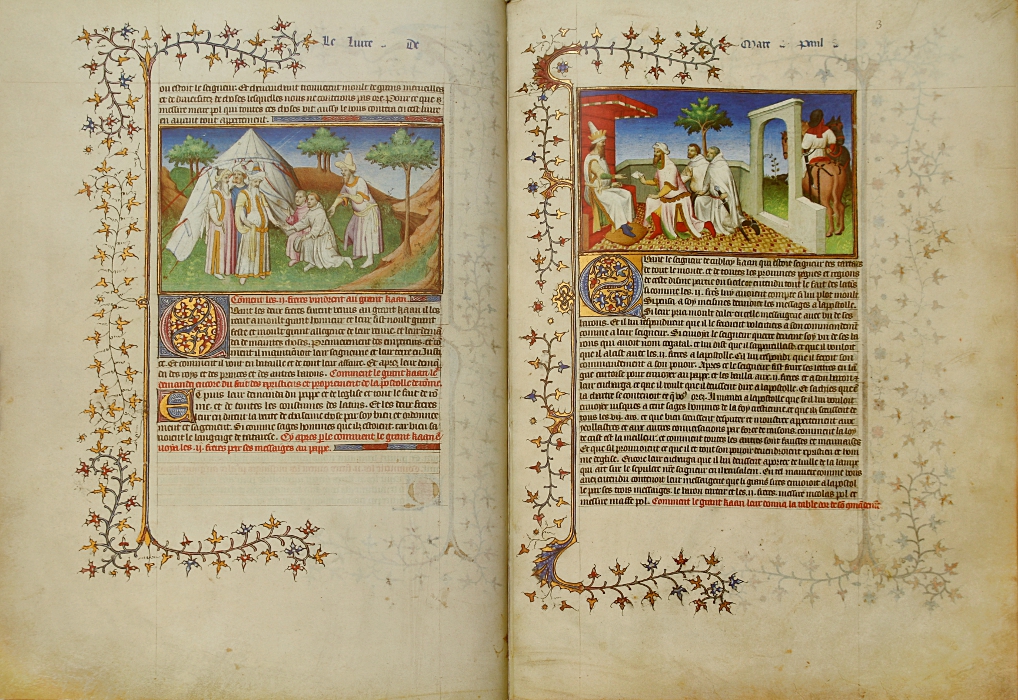

Le Livre des merveilles et autres récits de voyages et de textes sur l’Orient est un manuscrit enluminé réalisé en France vers 1410-1412. Il s'agit d'un recueil de plusieurs textes évoquant l'Orient réunis et peints à l'attention de Jean sans Peur, duc de Bourgogne, contenant le Devisement du monde de Marco Polo ainsi que des textes d'Odoric de Pordenone, Jean de Mandeville, Ricoldo da Monte Croce et d'autres textes traduits par Jean le Long. Le manuscrit contient 265 miniatures réalisées par plusieurs ateliers parisiens. Il est actuellement conservé à la Bibliothèque nationale de France sous la cote Fr.2810.

Le manuscrit, peint vers 1410-1412, est destiné au duc de Bourgogne Jean sans Peur, dont les armes apparaissent à plusieurs reprises (écartelé aux 1 et 4 de France à la bordure componée d’argent et de gueules, aux 2 et 3 bandé d’or et d’azur à la bordure de gueules), ainsi que ses emblèmes (la feuille de houblon, le niveau, le rabot). Son portrait est représenté au folio 226, repeint sur un portrait du pape Clément V. Le manuscrit est donné en janvier 1413 par le duc à son oncle Jean Ier de Berry, comme l'indique l'ex-libris calligraphié en page de garde. L'écu de ce dernier est alors repeint à plusieurs endroits sur celui de son neveu. Le livre est signalé dans deux inventaires du prince en 1413 et 1416. À sa mort, le livre est estimé à 125 livres tournois1.

Le manuscrit est ensuite légué à sa fille Bonne de Berry et à son gendre Bernard VII d'Armagnac. Il reste dans la famille d'Armagnac jusqu'aux années 1470. Il appartient à Jacques d'Armagnac lorsqu'une miniature est ajoutée au folio 42v. et son nom ajouté à l'ex-libris de la page de garde. Arrêté et exécuté en 1477, sa bibliothèque est dispersée et l'emplacement du manuscrit est alors inconnu. Un inventaire de la bibliothèque de Charles d'Angoulême mentionne un Livre des merveilles du monde qui pourrait être celui-ci. Il se retrouve ensuite peut-être dans la bibliothèque privée de son fils, le roi François Ier. Avec le reste de ses livres, il entre dans la seconde moitié du xvie siècle dans la bibliothèque royale et il est mentionné dans l'inventaire de Jean Gosselin.

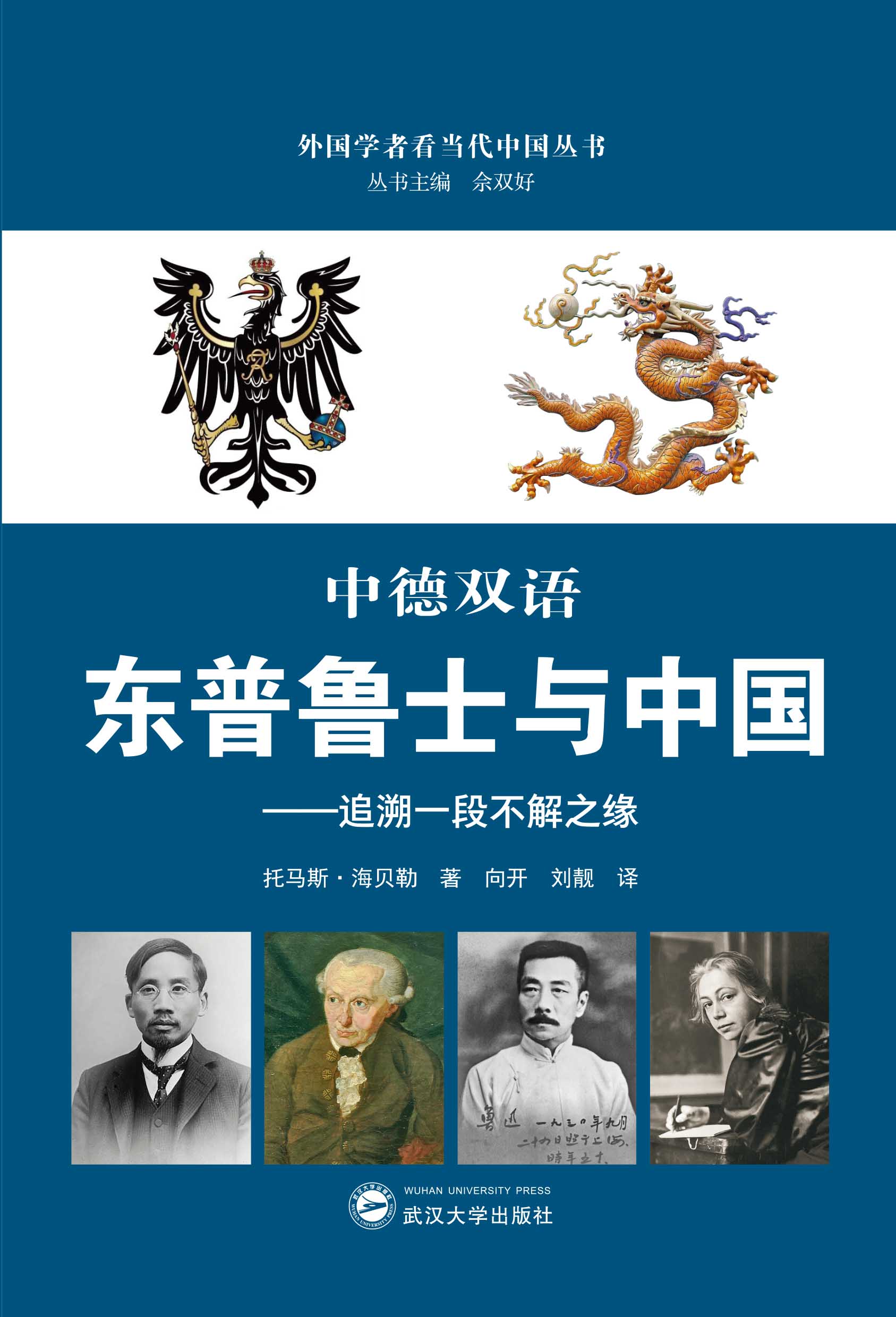

内容简介:

托马斯·海贝勒教授撰写的《东普鲁士与中国——追溯一段不解之缘》一书以东普鲁士与中国的深远关系为切入点,紧密结合了笔者的个人经历与职业背景,多层次、多角度地展示了一段至今仍未受到足够重视,未足够曝光的历史,寄望以这种方式丰富东普鲁士的记忆文化。 全书内容嵌在传记式的家族记忆框架里,读者可由此窥探笔者同中国、同东普鲁士之间的渊源,进而了解在探究这一主题过程中笔者的个人追求、兴趣和希冀。书中涉及大量具体的记忆形象和他(它)们与中国的联系,既包括与中国相关的人物,如中国研究学者、高级军官、外交官、传教士、建筑师,也包括出生在东普鲁士的思想家、科学家、艺术家、作家和诗人对中国产生的影响,还有那些研究解读他们思想精神的中国人,以及当地犹太人逃亡中国的历史等。海贝勒教授的追根溯源早已不囿于某个家族,而是立足中德双向视角,成功展现了一段延续至今,层次丰富的地区交往史。本书不涉及政治倾向性内容。

作者序:

如果作为研究中国的学者就东普鲁士与中国的关系撰文,绝不纯粹出于历史研究的学术兴趣,母亲家族与东普鲁士的渊源是我人生和身份的一部分,尽管我并不是在那里看到这个世界的第一缕光亮。母亲对东普鲁士的记忆深深烙印在我的脑海里,强化了我对自己这一层身份的认同,下文对此还将详述。

家族记忆是记忆文化的组成部分,在一个家族里它以这样的形式世代传承,影响着族人们的世界观和个人行为。(因萨尔茨堡新教流亡者身份而)遭人排挤的体验,祖父为了认识更广阔的世界冲出东普鲁士村庄那一方局促天地的决然之举,还有东普鲁士人对东部(与其接壤各国)依然保有的真挚坦率等等,都是这份家族记忆和认知储备的一部分,只是这样的东普鲁士仅留存在某些人的记忆里,他们要么曾经与此有所关联或者尚有关联,要么在那里出生,又或是探究到其家族与东普鲁士之间的渊源。

撰写此书是为了追忆这个曾经的德国东部省份以及当地人民为中德关系所作出的贡献,但同时这也是对德国乃至欧洲“集体记忆”的一次记念。对历史事件和人物,对文化、艺术、科学、哲学、政治及经济各领域演进过程的回忆,都是记忆文化和集体记忆的一部分。记忆文化则有利于群体与身份意识的创建。

全书以东普鲁士与中国的深远关系为切入点,将笔者的个人经历与职业背景紧密结合在一起。

全书共分九章,导言之后的第二至第四章主要涉及以下内容:首先是作为家族记忆文化一部分的家族东普鲁士背景(埃本罗德与施洛斯伯格)和家族在东普鲁士的生活史;其次是我对2017年前往埃本罗德和施洛斯伯格(东普鲁士)的寻根之旅的一些思考;然后将讲述我的中国之路、我的职业和在中国最初接触到的那些与东普鲁士或普鲁士有关的人与事。第五章探讨的是东普鲁士与中国之间的关系以及究竟是什么将它们联系了起来,这里将谈到普鲁士的亚洲政策、腓特烈大帝的中国情结、德国留在中国的“遗产”(亦或说德国镇压义和团运动及殖民青岛所犯下的“罪行”更为合适?)以及东普鲁士王宫之内所谓“中国热”的意义。这一章还将特别关注纳粹主义带来的灾难,它迫使大量原本生活在东普鲁士的犹太人在条件允许的情况下逃往上海,也导致中国传奇元帅朱德之女朱敏被拘禁于东普鲁士的一所集中营,这两个事件都是我前文所界定的“伦理记忆文化”的重要组成部分。第六章主要讲述东普鲁士作为德国汉学发源地的问题和东普鲁士在华传教士的活动。

对思想“先贤”康德和赫尔德及其与中国的渊源,以及他们对现代中国和中国形象的形成发展所产生的影响本书也将专章论述(第七章)。最后在第八章将谈及一系列具有代表性的东普鲁士名人,包括自然科学家、作家、政治理论家、艺术家以及商人,他们当中有历史人物,但也不乏出生在东普鲁士,却并没有在那里成长的当代名人。本章提到的历史名人有天文学家、数学家尼古拉·哥白尼,数学家、物理学家克里斯蒂安·哥德巴赫,大卫·希尔伯特,赫尔曼·闵可夫斯基和阿诺德·索末菲,女版画家、雕塑家凯绥·珂勒惠支,女政治理论家汉娜·阿伦特,女革命家王安娜,还有出生于东普鲁士的共产国际代表亚瑟·埃韦特和亚瑟·伊尔纳(别名理查德·施塔尔曼)及其在中国的活动,以色列女政治家、作家利亚·拉宾,外交家阿瑟·齐默尔曼也在此列;当代名人则包括建筑师福尔克温·玛格,雕塑家、装置艺术家胡拜图斯·凡·登·高兹,电子音乐的先锋人物、“橘梦乐团”创始人埃德加·福乐斯以及美国传奇蓝调摇滚乐队“荒原狼”主唱约阿希姆·弗里茨·克劳雷达特(约翰·凯)等。出现在本书中的还有海因里希·冯·克莱斯特和托马斯·曼的东普鲁士岁月,著名的尼达艺术家之村,以及多位在中国曾经或依然被关注研究(接受)的东普鲁士名人,他们当中有同中国有生意往来的商贾,也有二战中既在东普鲁士又在中国抗日战场参战的苏联元帅。部分苏联军队在东普鲁士的表现一定程度上与其1945年在中国东北的所作所为相似,这一切分别存留在德国和中国民众的集体记忆里,或许正是这些使许多中国人在面对东普鲁士平民的悲剧时多少有些感同身受。

本书并不着力探究普鲁士与中国交往的历史,对此学者们已有著述,这里更多关注的是与那个曾经属于德国,如今分属俄罗斯、波兰和立陶宛的省份,以及与此相关的记忆形象和他(它)们与中国的缘分,既包括与中国有联系的人物、中国问题学者、高级军官、外交官、传教士、建筑师,也包括出生在东普鲁士的思想家、科学家、艺术家、作家和诗人对中国产生的影响,还有那些研究解读他们思想精神的中国人,以及当地犹太人逃亡中国的历史等。本书无意全面探究所有这些联系,对笔者而言关键是对这些记忆形象的收录整理,不拘泥于细节,本来写作初衷就是以勾勒轮廓框架为先,勘明趋势与特征,并非还原事件经过。全书内容嵌在传记式的家族记忆框架里,读者可由此窥探笔者同中国、同东普鲁士之间的渊源,进而了解在探究这一主题过程中笔者的个人追求、兴趣和希冀,这些传记性内容见于本书第二章,第三章则是在此框架下对“故乡”概念的简短反思——探讨究竟何为“故乡”。总之,撰写这本书是一次尝试,尝试记录东普鲁士乃至德国的一段历史,一段至今仍未受到足够重视,未足够曝光的历史,寄望以这种方式去丰富东普鲁士的记忆文化。

东普鲁士在其历史上既是一个多民族地区,也是一个移民地区。条顿骑士团(亦称德意志骑士团)东征前,西波罗的海沿岸地区生活着古普鲁士人。在骑士团间或野蛮的殖民过程中,来自德意志帝国的拓荒者不断涌入,此外还有斯堪的纳维亚人、瑞士人、波兰人、俄罗斯人、捷克人、法国人和受洗的立陶宛人,他们与当地原住民聚居融合,14世纪又有不少马祖里人、立陶宛人和鲁提尼人迁居于此。随着15世纪条顿骑士团历经一系列损失惨重的战役走向没落,来自波兰、俄国和立陶宛的移民在此安家落户。伴随着宗教改革运动,欧洲第一个新教国家普鲁士公国建立,更广泛的宗教自由吸引了整个欧洲的新教和加尔文教派信徒,他们不仅来自德意志帝国,还从波兰、立陶宛、荷兰、法国(胡格诺教派信徒)、苏格兰、俄国、奥匈帝国迁徙而来,甚至还有主要由俄国而来的犹太人。

17世纪塔塔尔族人的袭扰和1709年至1711年间泛滥的鼠疫造成东普鲁士全境人口锐减,于是普鲁士国王着力推动瑞士加尔文派信徒以及萨尔兹堡的新教流亡者来本国定居,这两大群体中的大部分人都是熟练工匠。此举造成东普鲁士居民来源复杂多样,使建立德语教育机构和使用德语授课成为促进这些移民群体统一与融合的手段,这个目标遂成为腓特烈·威廉一世1713年引入普通义务教育的原因之一。

无论是当地非德意志的原生民族,还是来自四面八方的移民,都为东普鲁士增添了新的元素,对它产生了影响,进而在这片土地上留下各自的印迹,为其发展和多元化贡献了自己的力量。此外,在东普鲁士的历史上,该地区始终与波兰、俄国和波罗的海诸国保持着紧密的关系和深入的交流。对此阿明·缪勒-斯塔尔是这样说的:交织在一起的关系网“层层叠叠,密密实实”,在造就多元文化精英方面功不可没。

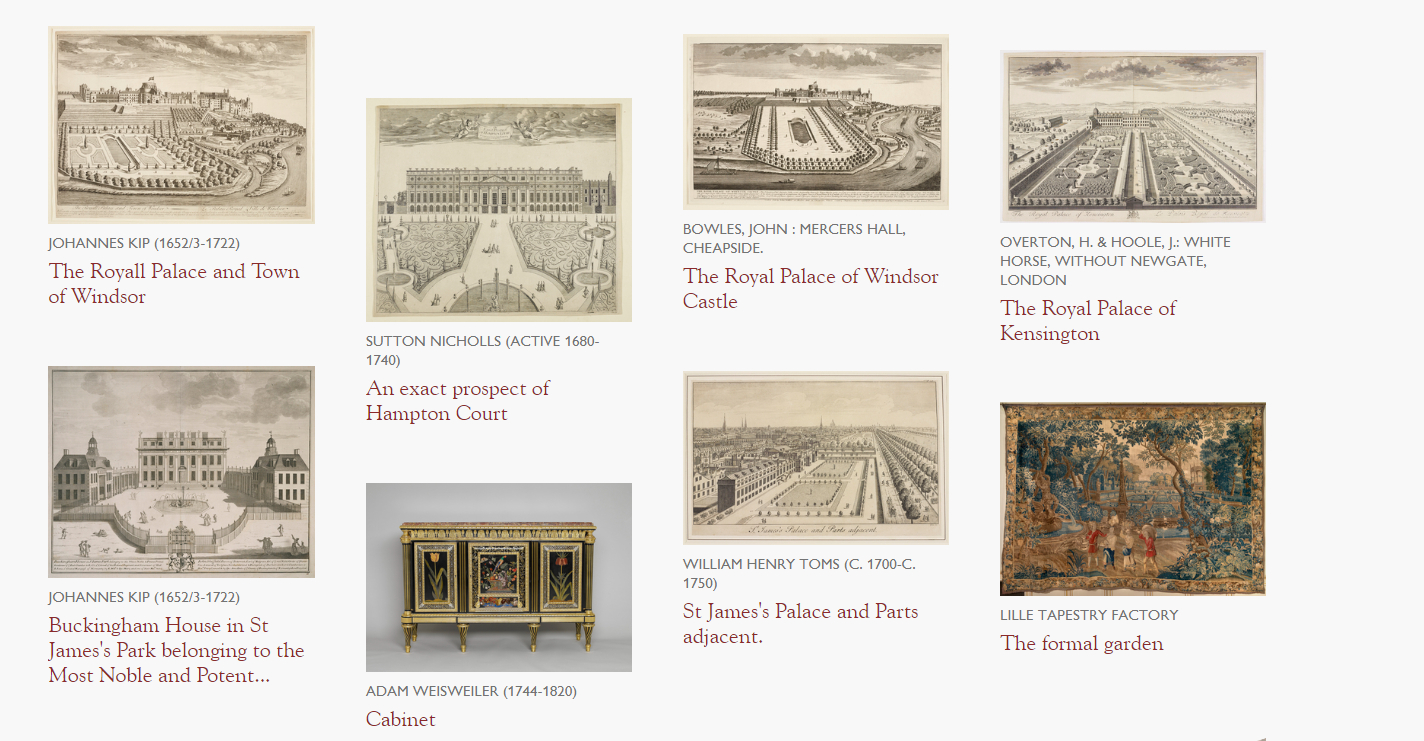

The Château de Marly, bought by Louis XIV in 1679, can be seen at the head of a great central canal flanked by twelve guest pavilions. Extensive efforts were expended in the creation of the garden at Marly, through the drainage of the marshy terrain, the engineering of the water features and the excavation of whole sections of valley floor. None of this is suggested in this painting which conveys instead effortless control over nature.

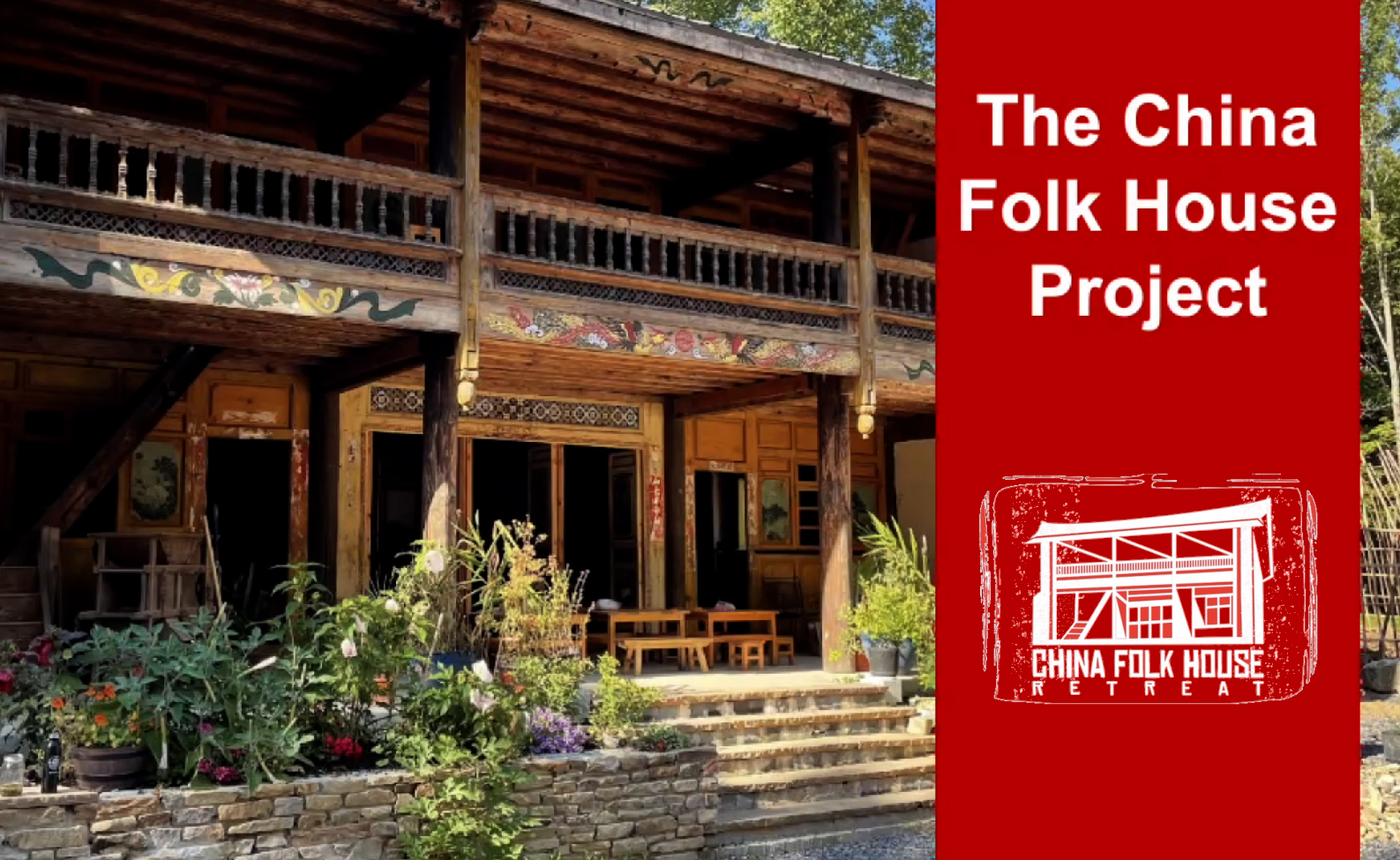

The China Folk House Retreat is a Chinese folk house in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, United States, reconstructed from its original location in Yunnan in China. A non-profit organization dismantled and rebuilt it piece by piece with the goal to improve U.S. understanding of Chinese culture.

History

John Flower, director of Sidwell Friends School's Chinese studies program, and his wife Pamela Leonard started bringing students to Yunnan in 2012 as part of a China fieldwork program. In 2014 Flower, Leonard, and their students found the house in a small village named Cizhong (Chinese: 茨 中) in Jianchuan County of Yunnan, China. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, they brought dozens of 11th and 12th-grade students to Yunnan to experience the cultural and natural environment of this province every spring. The architectural style of this house is a blend of Han, Bai, Naxi and Tibetan styles.

The Cizhong Village is located in eastern Himalaya, alongside the Mekong River. It has a long history of Sino-foreign cultural exchanges. The Paris Foreign Missions Society established the Cizhong Catholic Church in 1867. When they visited the village, Zhang Jianhua, owner of the house, invited them to his home. Zhang told them that the house was built in 1989, and would be flooded by a new hydroelectric power station. While the government built a new house for him one kilometer away, Flower came up with the idea of dismantling the house and rebuilding it in the United States. This house was built using mortise and tenon structure, which made it easy to be dismantled.

Logistics

Flower and his students visited Zhang several times and eventually bought the house from him. After measurements and photographing, the whole house was dismantled, sent to Tianjin and shipped to Baltimore, and finally to West Virginia. Since 2017, they have spent several years rebuilding the house in Harpers Ferry, at the Friends Wilderness Center, following the traditional Chinese method of building. For the development of this project, Flower and Leonard formed the China Folk House Retreat.

Addison, Joseph and Richard Steele ed. The Spectator no. 37, 12 April 1712.

Alayrac-Fielding, Vanessa. “Dragons, clochettes, pagodes et mandarins : Influence et représentation de la Chine dans la culture britannique du dix-huitième siècle (1685-1798)”, unpublished PhD thesis, Université Paris 7 Denis Diderot, Paris

---. “Frailty, thy Name is China: Women, Chinoiserie and the threat of low culture in 18th-century England.”Women’s History Review 18:4 (Sept 2009): 659-668.

---. “De l’exotisme au sensualisme : réflexion sur l’esthétique de la chinoiserie dans l’Angleterre du XVIIIe siècle.”In Pagodes et Dragons : exotisme et fantaisie dans l’Europe rococo. Ed. Georges Brunel. Paris: Paris Musées, 2007. 35-41

Ayers, John, Impey, Olivier and J.V.G Mallet. Porcelain for Palaces: the Fashion for Japan in Europe 1650-1750. London: Oriental Ceramic Society, 1990.

Ballaster, Ros. Seductive Forms: Women’s Amatory Fiction from 1684 to 1740. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Baridon, Michel. “Hogarth’s ʽliving machines of nature’ and the theorisation of aesthetics.”In Hogarth. Representing Nature’s Machines. Eds. David Bindman, Frédéric Ogée, and Peter Wagner. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001. 85-101.

Belevitch-Stankevitch, Hélène. Le Goût chinois en France. 1910. Genève: Slatkine, 1970.

Benedict,Barbara. “The Curious Attitude in Eighteenth-Century Britain: Observing and Owning.”Eighteenth-Century Life 14 (Nov. 1990): 75.

Burnaby,William. The Ladies’ Visiting-Day. London, 1701.

Bony, Alain. Léonora, Lydia et les autres : Etudes sur le (nouveau) roman. Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon, 2004.

Bray, William (ed.). The Diary of John Evelyn, Esq. London/New York: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, 1818.

Charleston, Robert J. “Porcelain as a Room Decoration in Eighteenth-Century England.”Magazine Antiques 96 (1969): 894- 96.

Chen, Jennifer, Julie Emerson and Mimi Gates (eds.). Porcelain Stories: From China to Europe. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

Climenson, Emily (ed.). Passages from the Diaries of Mrs. Philip Lybbe Powys of Harwick House, Oxon (1756-1808). London: Longmans & Green, 1899.

Clunas, Craig (ed.). Chinese Export Art and Design. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1987.

Collet-White, James (ed.). Inventories of Bedfordshire Country Houses 1714-1830. The Publication of the Bedfordshire Historical Record Society, 74 (1995).

William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World. London: James Knapton,1687.

Defoe, Daniel. A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain 1724-1726. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986.

Fowkes Tobin, Beth. “The Duchess’s Shells : Natural History Collecting, Gender, and Scientific Practice.”In Material Women, 1750-1950. Eds. Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin. London: Ashgate, 2009. 301-325.

Freud, Sigmund. “Fetishism.”In Sigmund Freud: the Penguin Reader. Ed Adam Phillips. Harmondsworth : Penguin Books, 2006. 91-93.

Hallé, Antoinette (ed.). De l’immense au minuscule. La virtuosité en céramique. Paris : Paris musées, 2005.

Hind, Charles (ed.). The Rococo in England. A symposium. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1986.

Hogarth, William. The Analysis of Beauty, Written With a View of Fixing the Fluctuating Ideas of Taste. 1753. Ronald Paulson ed. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1997.

Honour, Hugh. Chinoiserie: the Vision of Cathay. London: Murray, 1961.

Impey, Oliver. Chinoiserie: the Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration. New York: Scribner, 1977.

Impey, Oliver and Arthur MacGregor (eds.) The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe. Oxford: Clarendon, 1985.

Impey, Oliver. “Collecting Oriental Porcelain in Britain in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries.”In The Burghley Porcelains, an Exhibition from the Burghley House Collection and Based on the 1688 Inventory and 1690 Devonshire Schedule. New York: Japan Society, 1990. 36-43.

Impey, Oliver and Johanna Marshner. “ʽChina Mania’: A Reconstruction of Queen Mary II’s Display of East Asian Artefacts in Kensington Palace in 1693.”Orientations 29:10 (November 1998): 60-61.

Jackson-Stops, Gervase (ed.) The Fashioning and Functioning of the British Country House, Studies in the History of Art 25. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1989.

Kerr, Rose. “Missionary Reports on the Production of Porcelain in China.”Oriental Art, 47: 5 (2001): 36-37.

Kowaleski-Wallace, Elizabeth. Consuming Subjects: Women, Shopping, and Business in the 18th Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Laird, Mark (ed.). Mrs Delany and her Circle. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Langley, Batty. Practical Geometry, Applied to the Useful Arts of Building. London: W. & J. Innys and J. Osborn, 1726.

Llanover, Lady (ed.) The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany, 6 vols. London, 1860-61.

Lévi-Strauss Claude. Le Cru et le cuit. Paris : Plon, 1964.

Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.1690. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 2004.

Lunsingh Scheurleer. T.H. “Documents on the Furnishing of Kensington House.”Walpole Society 38 (1960-1962): 15-58.

Minguet, Philippe. L’Esthétique du rococo. Paris: Vrin, 1966.

Moore, Edward (ed.). The World n° 38 (20 September 1753).

Murdoch, Tessa. Noble Households. Eighteenth-Century Inventories of Great English Houses. Cambridge: John Adamson, 2006.

Ostergard, Derek (ed.). William Beckford, 1760-1844: An Eye for the Magnificent. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001.

Park, William. The Idea of Rococo. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1993.

Pierson, Stacey. Collectors, Collections and Museums: The Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560-1960. Bern: Peter Lang, 2007.

Pietz William. “The Problem of the Fetish, I.”Res 9 (Spring 1985). 5-17

DOI : 10.1086/RESv9n1ms20166719

---. »The Problem of the Fetish, II: the Origin of the Fetish,“Res 13 (Spring 1987). 23-45.

Pomian, Krzysztof. Collectionneurs, amateurs et curieux, Paris, Venise : xvie-xviiie siècle, Paris : Gallimard, 1987.

Porter, David. The Chinese Taste in England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

---. ”Monstrous Beauty: Eighteenth-Century Fashion and the Aesthetics of the Chinese Taste.“Eighteenth-Century Studies 35:3 (2002): 395-411.

Rigby, Douglas and Elizabeth Rigby. Lock, Stock, and Barrel: The Story of Collecting. London: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1944.

Smith, Charles Saumarez. The Rise of Design: Design and the Domestic Interior in Eighteenth-Century England. London: Pimlico, 2000.

Shaftesbury, Earl of. Soliloquy: or, Advice to an Author. London: John Morphew, 1710.

Shulsky, Rosenfeld. ”The Arrangement of the Porcelain and Delftware Collection of Queen Mary in Kensington Palace.“American Ceramic Circle Journal 8 (1990): 51-74.

Sloboda, Stacey. ”Displaying Materials: Porcelain and Natural History in the Duchess of Portland’s Museum.“Eighteenth-Century Studies 43.4 (2010): 455-472.

DOI : 10.1353/ecs.0.0159

Sloboda, Stacey. ”Porcelain Bodies: Gender, Acquisitiveness and Taste in 18th-century England.“. In Material Cultures, 1740-1920. Eds. John Potvin and Alla Myzelev. London: Ashgate, 2009. 1-36.

Snodin, Michael (ed.). Rococo Art and Design in Hogarth’s England. London: V&A Publication, 1984.

Snodin, Michael and Cynthia Roman (eds.). Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Stalker, John and George Parker. Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing Being a Complete Discovery of these Arts. Oxford, 1688.

Wilson, Joan ”A Phenomenon of Taste: the Chinaware of Queen Mary II."Apollo 126 (August 1972): 116-123.

Young, Hilary. English Porcelain, 1745-1795: its Makers, Design, Marketing and Consumption. London: Victoria and Albert Publications, 1999.

Il Milione è il resoconto dei viaggi in Asia di Marco Polo, intrapresi assieme al padre Niccolò Polo e allo zio paterno Matteo Polo, mercanti e viaggiatori veneziani, tra il 1271 e il 1295, e le sue esperienze alla corte di Kublai Khan, il più grande sovrano orientale dell'epoca, del quale Marco fu al servizio per quasi 17 anni.

Il libro fu scritto da Rustichello da Pisa, un autore di romanzi cavallereschi, che trascrisse sotto dettatura le memorie rievocate da Marco Polo, mentre i due si trovavano nelle carceri di San Giorgio a Genova.

Rustichello adoperò la lingua franco-veneta, una lingua culturale diffusa nel Nord Italia tra la fascia subalpina e il basso Po. Un'altra versione fu scritta in lingua d'oïl, la lingua franca dei crociati e dei mercanti occidentali in Oriente, forse nel 1298 ma sicuramente dopo il 1296. Secondo alcuni ricercatori, il testo sarebbe poi stato rivisto dallo stesso Marco Polo una volta rientrato a Venezia, con la collaborazione di alcuni frati dell'Ordine dei Domenicani.

Considerato un capolavoro della letteratura di viaggio, Il Milione è anche un'enciclopedia geografica, che riunisce in volume le conoscenze essenziali disponibili alla fine del XIII secolo sull'Asia, e un trattato storico-geografico.[5] È stato scritto che «Marco si rivolge a tutti quelli che vogliono sapere: sapere quello che c'è al di là delle frontiere della vecchia Europa. Non mette il suo libro sotto il segno dell'utile, ma sotto il segno della conoscenza».

Rispetto ad altre relazioni di viaggio scritte nel corso del XIII secolo, come la Historia Mongalorum di Giovanni da Pian del Carpine e l'Itinerarium di Guglielmo di Rubruck, Il Milione fu eccezionale perché le sue descrizioni si spingevano ben oltre il Karakorum e arrivarono fino al Catai. Marco Polo testimoniò l'esistenza di una civiltà mongola stanziale e molto sofisticata, assolutamente paragonabile alle civiltà europee: i mongoli, insomma, non erano solo i nomadi "selvaggi" che vivevano a cavallo e si spostavano in tenda, di cui avevano parlato Giovanni da Pian del Carpine e Guglielmo di Rubruck, ma abitavano città murate, sapevano leggere, e avevano usi e costumi molto sofisticati. Così come Guglielmo di Rubruck, invece, Marco smentisce alcune leggende sull'Asia di cui gli Europei all'epoca erano assolutamente certi.

Il Milione è stato definito come "la descrizione geografica, storica, etnologica, politica, scientifica (zoologia, botanica, mineralogia) dell'Asia medievale".Le sue descrizioni contribuirono alla compilazione del Mappamondo di Fra Mauro e ispirarono i viaggi di Cristoforo Colombo.

The detail of the possessions of the Antonie family at their estate at Colworth House in Sharnbrook (Bedfordshire) in the 18th century, recorded in successive inventories, provides an interesting illustration of men’s taste for porcelain. Marc Antonie was steward to the Duke of Montagu. In 1715, he bought the Colworth estate from John Wagstaff, citizen and mercer of the City of London, who had previously bought it from the Montagus. The Antonies had invested money in the South Sea stock, which resulted in the family’s financial collapse when the South Sea Bubble burst. After Marc Antonie’s death in 1720, the 1723 inventory was made with a view to selling the furniture to get the family out of debt. The presence in the inventory of porcelain dishes and basins exported from China reflects how the fashion for porcelain was connected to the ever more fashionable practice of drinking another Chinese product, tea and, to a lesser degree, coffee. The inventory records a “cheany & Teatable” in the North Parlour, advertised for £ 6 14s, and in the Hall “10 little Cheany plates that sold for £ 1 5s, 6 larg [sic] Cheany Dishes £ 1 15s, 4 Cheany Basons, Cheany mugs and Delf Dishes, Cheany Cassters and Cheany”.

The second inventory of 1771 was made after the death of Marc Antonie’s youngest son, Richard, on 26 November 1771. Richard Antonie had inherited the estate in 1768 after John’s death, Marc Antonie’s eldest son. He first established himself as a draper and then moved on to Jamaica in 1748 where he owned a sugar plantation. The furnishings of the house listed in the 1771 inventory were mostly purchased by Richard and some pieces by John Antonie. They give a good indication of the type of furnishing found in the 1760s in a country house, and, as James Collett-White points out, “reflect what a country gentleman with London connections might have purchased and collected”.

Ornamental and functional porcelain figures prominently in the inventory. Antonie had an unusually large collection of china. In the two parlours and three of the four principal bedrooms were 125 pieces of ornamental china. The inventory does not mention the provenance of the pieces and it is highly probable these porcelains were not all of Chinese origin, but would have also come from continental centres such as Delft, Meissen and France, and also from English porcelain factories such as Derby, Worcester and Bow. Non-functional porcelain was completed by a huge number of porcelain plates and dishes which were kept in the “china closet”. Two “dragon china” dishes and “Nankeen basins” get mentioned in the inventory, which confirms the presence of Chinese export porcelain in Antonie’s collection. The taste for Chinese-styled indoor and outdoor decoration, which blended authentic Chinese wares with chinoiserie, gained momentum in the century, reaching a peak in the 1750s and 1760s16. Antonie had a particular liking for chinoiserie, as he commissioned a gate or possibly a low fence of oak railings to be made in the Chinese style, which he mentioned in his notes: “Richard Antonie made a New China Work the front of his house.”It thus appears very likely that he would have collected Chinese porcelain to complement the Chinese theme set up outside his house.

The foundation of the East India Company in 1600 made direct trade with China possible and led to an increase in English imports of Chinese wares. Although Chinese porcelain started to reach England in higher quantities at that time, they continued to be considered as precious exotica worthy of display in cabinets of curiosities. Most Chinese porcelain imported in the 17th century consisted of blanc-de-Chine and blue and white ware. Brown Yixing stoneware was also imported, as well as monochrome-glazed porcelain1. In the middle of the 17th century, direct trade with China was hampered by wars of succession within the Chinese empire, which led the East India Company to find other indirect ways of buying Chinese porcelain, and also, from 1657, to turn to Japan for more supplies in porcelain. The imports of Japanese overglazed enamelled porcelain in England provided collectors with porcelain ware of a new type: colours and new compositional patterns hitherto unknown entered English interiors2. Europe’s long-lasting fascination for porcelain can be ascribed to its beauty, its exotic provenance and the secrets surrounding its fabrication. Indeed, the manufacture of porcelain remained a mystery until the 18th century in Europe, when the alchemist Johann Böttger first succeeded in creating a porcelain body of the same type as that made in China for the Meissen factory. Until that time, porcelain had been thought to come from shells. The original Italian term porcellana, meaning “conch shell”, reflects this long-held belief3. At the end of the 17th century, speculations about its composition still ran high, as is shown by Captain William Dampier’s remark on the origin of porcelain:

The Spaniards of Manila, that we took on the Coast of Luconia, told me, that this Commodity is made of Conch-shells; the inside of which looks like Mother of Pearl. But the Portuguese lately mentioned, who had lived in China, and spoke that and the neighbouring Languages very well, said, that it was made of a fine sort of Clay that was dug in the Province of Canton. I have often made enquiry about it, but could never be well satisfied in it.

The association between porcelain and shells was further evidenced in the common practice of displaying shells and porcelain together in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Duchess of Portland had a famous collection of shells and of unique pieces of porcelain, an association which contributed to blurring the boundary between naturalia and artificialia

Porcelain first occupied a non-functional status in the cabinets of rarities and curiosities of English aristocrats5. The famous collector John Tradescant published in 1656 the first catalogue of his collection, which listed “idols from India, China and other pagan lands”6. He also possessed porcelain, some mounted with silver and gold. In the 17th century, rare and precious porcelain items were often mounted with expensive metalwork, a practice that was common throughout Europe. The Duchess of Cleveland’s collection, which was sold in France in 1672, contained very fine Chinese and Japanese pieces, according to the Mercure Galant in July 1678 : “l’élite des plus belles porcelaines que plusieurs vaisseaux de ce pays [l’Angleterre] y avaient apportées pendant plusieurs années de tous les lieux, où ils avaient accès pour leur commerce.”The Duchess’s finest porcelain pieces were gilt-mounted : “il y en avait d’admirables par leurs figures, par les choses qui étaient représentées dessus et par la diversité de leurs couleurs. Les plus rares étaient montées d’or ou de vermeil doré et garnies diversement de la même manière en plusieurs endroits”7. The adding of expensive, luxurious silver or gold mounts to the porcelain body of an object visually reinforced the latter’s precious status in the cabinet of curiosities. It also celebrated the transformative powers of artistic creation. Not unlike the popular mounted nautilus cup that stood in cabinets of rarities and curiosities, mounted porcelain held the reference to its artistic manufacture together with the allusion to its natural origin. The perceived shell-like substance of the object had undergone two transformations: it had first been moulded and fired by Oriental craftsmen to be turned into a piece of porcelain, and had then been further transformed and enhanced with precious metal by European craftsmen. Porcelain wares thus fitted into larger collections which included naturalia and artificialia, classical works of art, antiquities as well as more unusual curiosities. Although the passion for collecting porcelain was already closely connected to the realm of the feminine in the 17th century, it would be wrong to assume that men did not collect oriental porcelain. On a visit to a Mr Bohun on 30 July 1682 at Lee in Kent, John Evelyn noted the couple’s joint appreciation of Chinese and Japanese wares. The house possessed a lacquered cabinet, and it is likely that the lady’s cabinet which gets mentioned, was a china closet:

Went to visit our good neighbour, Mr. Bohun whose whole house is a cabinet of all elegancies, especially Indian; in the hall are contrivances of Japan screens, instead of wainscot; […] The landscapes of the screens represent the manner of living, and country of the Chinese. But, above all, his lady’s cabinet is adorned on the fret, ceiling, and chimney-piece, with Mr. Gibbons’ best carving. (Bray ed. 173). Quelle:Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The china closet and, by extension, the Lady’s dressing room where oriental porcelain was displayed, were often compared to an oriental temple, but were also seen as an emblematic temple of femininity. The female closet where porcelain, shells and sometimes books, were stored served as an instrument of female sociability, an intimate gynocentric space where women could exchange their knowledge and expertise. The visits paid by women to their respective homes often led to the inspection of the china closet and fuelled discussions on porcelain. Lady Dashwood, for example, asked for Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys’s opinion on oriental porcelain displayed in her china closet at Kirtlington Park: “Her Ladyship said she must try my judgment in china, as she ever did all the visitors of that closet, as there was one piece there so much superior to the others. I thought myself fortunate that a prodigious fine old Japan dish almost at once struck my eye”(Climenson 198). The china cabinet functioned as a female museum, as was explained in an essay from the World:

You are not to suppose that all this profusion of ornament is only to gratify her own curiosity: it is meant as a preparative to the greatest happiness of life, that of seeing company. And I assure you she gives above twenty entertainments in a year to people for whom she has no manner of regard, for no other reason in the world than to shew them the house. [I am] continually driven from room to room, to give opportunity from strangers to admire it. But as we have lately missed a favourite Chinese tumbler, and some other valuable moveables, we have entertained thoughts of confining the shew to one day in the week, and of admitting no persons whatsoever without tickets.

The exchange and display of porcelain allowed women to circumscribe an artistic practice and field of expertise of their own. It gave them authority in the realm of domestic interior decoration as well as in that of scientific knowledge. In her analysis of the Duchess of Portland’s collection of porcelain and shells, Stacey Sloboda has shown how the collection and display of naturalia ‒shells‒ and artificialia –porcelain‒ connected natural history to art, and argued that porcelain occupied an intermediary position, as both exotic curiosity and manufactured object, “complicat[ing] the binary of ”raw“ imperial specimens versus ”cooked“ Western objects of connoisseurship” (Sloboda 467). The china closet decorated with shells thus merged natural history and decorative arts. It can also be read, I suggest, in terms of narration and architecture. Women read exotic stories on the surfaces of oriental porcelain but the authority they exerted over the display of porcelain wares also transformed them into authors. David Porter has argued that the decorative patterns of transitional porcelain wares of the Ming and early Qing dynasties often represented women in ideal garden scenes. He proposes to read these scenes of female communities evolving in peaceful natural surroundings depicted on Chinese porcelain as contemporaneous analogues of female utopias and Sapphic literary works that developed in English literature in the last decades of the 17th and early 18th centuries. Porcelain surfaces read by elite women nurtured their dreams of female academies, retreats and friendly communities.

Quelle:Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

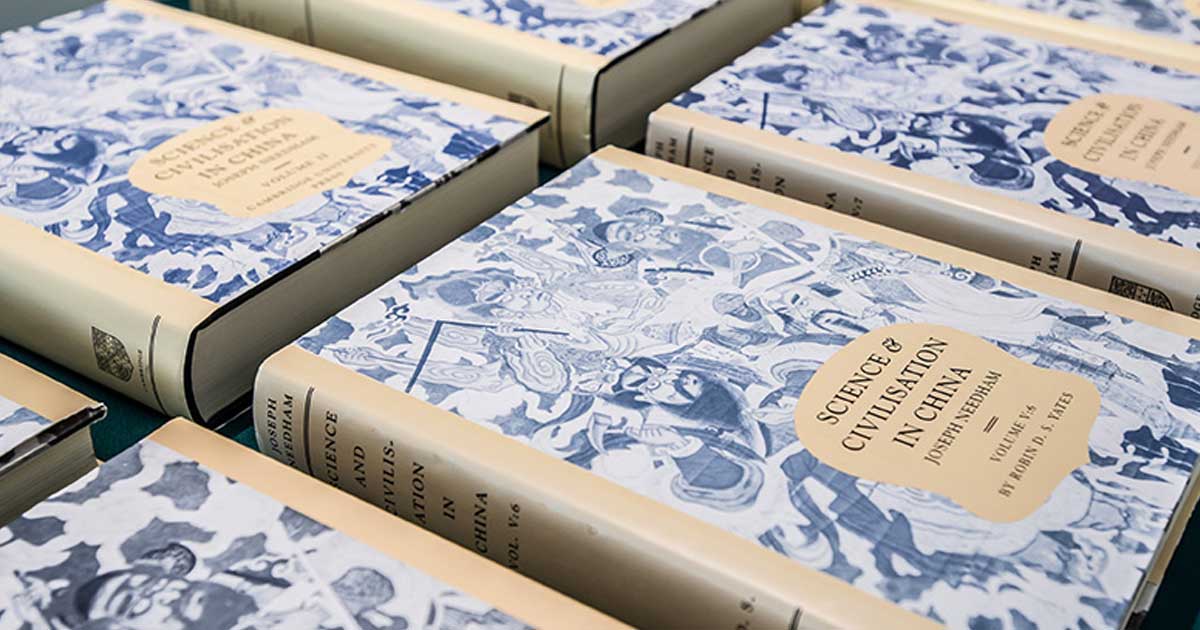

Die von dem britischen Biochemiker Joseph Needham (1900–1995) initiierte und anfangs herausgegebene englischsprachige Buchreihe zur Wissenschaft und Kultur in China setzte neue Maßstäbe in der Beschäftigung mit China im Wissenschaftsbereich. Als Standardwerk zur chinesischen Wissenschafts- und Technikgeschichte veränderte es die Wahrnehmung Chinas durch die westliche Welt und lenkte die Aufmerksamkeit auf die historischen wissenschaftlichen und technologischen Leistungen Chinas. Joseph Needham hatte das von ihm initiierte Projekt von 1954 an bis zu seinem Tod 1995 koordiniert. Zu Lebzeiten erschienen 17 Bände, weitere sieben Bände wurden seither durch das von Needham begründete Needham Research Institute herausgegeben. Das Erscheinen weiterer Bände ist in Vorbereitung. Die Gesamtanlage des Werkes ist etwas schwer zu überblicken. Die folgende Übersicht erhebt keinen Anspruch auf Aktualität oder Vollständigkeit.

| Band | Titel | Autor(en) | Jahr | Anm. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vol. 1 | Introductory Orientations | Wang Ling (research assistant) | 1954 | |

| Vol. 2 | History of Scientific Thought | Wang Ling (Forschungsassistent) | 1956 | OCLC 19249930 |

| Vol. 3 | Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth | Wang Ling (Forschungsassistent) | 1959 | OCLC 177133494 |

| Vol. 4, Part 1 |

Physics and Physical Technology Physics |

Wang Ling (Forschungsassistent), with cooperation of Kenneth Robinson | 1962 | OCLC 60432528 |

| Vol. 4 Part 2 |

Physics and Physical Technology Mechanical Engineering |

Wang Ling (collaborator) | 1965 | |

| Vol. 4, Part 3 |

Physics and Physical Technology Civil Engineering and Nautics |

Wang Ling and Lu Gwei-djen (collaborators) | 1971 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 1 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Paper and Printing |

Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin | 1985 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 2 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator) | 1974 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 3 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Historical Survey, from Cinnabar Elixirs to Synthetic Insulin |

Ho Ping-Yu and Lu Gwei-djen (collaborators) | 1976 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 4 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus and Theory |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator), with contributions by Nathan Sivin | 1980 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 5 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Physiological Alchemy |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator) | 1983 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 6 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Military Technology: Missiles and Sieges |

Robin D.S. Yates, Krzysztof Gawlikowski, Edward McEwen, Wang Ling (collaborators) | 1994 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 7 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic |

Ho Ping-Yu, Lu Gwei-djen, Wang Ling (collaborators) | 1987 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 8 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Military Technology: Shock Weapons and Cavalry |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator) | 2011[1] | |

| Vol. 5, Part 9 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Textile Technology: Spinning and Reeling |

Dieter Kuhn | 1988 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 10 |

"Work in progress" | |||

| Vol. 5, Part 11 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Ferrous Metallurgy |

Donald B. Wagner | 2008 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 12 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Ceramic Technology |

Rose Kerr, Nigel Wood, contributions by Ts'ai Mei-fen and Zhang Fukang | 2004 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 13 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Mining |

Peter Golas | 1999 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 1 |

Biology and Biological Technology Botany |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator), with contributions by Huang Hsing-Tsung | 1986 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 2 |

Biology and Biological Technology Agriculture |

Francesca Bray | 1984 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 3 |

Biology and Biological Technology Agroindustries and Forestry |

Christian A. Daniels and Nicholas K. Menzies | 1996 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 4 |

Biology and Biological Technology Traditional Botany: An Ethnobotanical Approach |

Georges Métailie | 2015 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 5 |

Biology and Biological Technology Fermentations and Food Science |

Huang Hsing-Tsung | 2000 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 6 |

Biology and Biological Technology Medicine |

Lu Gwei-djen, Nathan Sivin (editor) | 2000 | |

| Vol. 7, Part 1 |

Language and Logic | Christoph Harbsmeier | 1998 | |

| Vol. 7, Part 2 |

General Conclusions and Reflections | Kenneth Girdwood Robinson (editor), Ray Huang (collaborator), introduction by Mark Elvin | 2004 | OCLC 779676 |

The china closet can also be read in terms of architecture, as a monument to the idea of rococo. If natural science was given pride of place in the space of the closet, the feminine accents of the rococo style also sprang up in the curvaceous lines of rocks, shells and porcelain dishes completed by glittering ornaments. Shells and porcelain have traditionally stood for women, as the well-documented comparison between women and porcelain throughout the 18th century testifies.29 The china closet, either a simple cabinet or a room, can be understood as a sign of the feminisation and rococo-isation of interior decoration. The idea of rococo pervaded 18th century European culture and, despite contrasted views of scholarship about its periodisation, may be seen to emerge in the early 18th century and evolve until the late 1760s.30 The rococo style has been assumed to have reached England in the decorative arts in the 1740s but the new hybrid genre of the novel, characterised by its interplay of various literary sources and genres (romances, drama, biographies, histories) has also been identified with the idea of rococo.31 The aspect of the china closet adorned with shells, a result of female handicraft, may not strictly correspond to the lavish rococo interior decoration of a French 18th-century boudoir, but signals, I am suggesting, the rococo-isation of English interiors. Arguably, the scantiness of surviving evidence about the display of female china closets, glimpsed though examples in female correspondence or diaries, only leads to hypothetical interpretations. However, the numerous satires on the fashion for female china closets found in the periodical press of the period help reconstruct a practice that must have been popular among the aristocracy and wealthy middle classes. I propose here to examine the rococo aesthetic of the female china closet by crossing contemporary references to real china closets with an analysis of two periodical essays, the first from The Spectator published in 1712, the second being the essay previously cited (The World, 38), published in 1753. This comparative study will enable me to show the evolution of the rococo’s imprint on English interiors.

In Joseph Addison’s Spectator essay number 37, dated 12 April 1712, the fictional persona of Mr. Spectator recounts his visit to an aristocratic widow’s library. The essay aligns Leonora’s reading tastes with female chinamania, depicting the lady’s library, in the narrator’s eyes, as a hybrid and counter-natural piece of furniture decorated with Chinese porcelain:

At the End of the Folio’s (which were finely bound and gilt) were great Jars of China placed one above another in a very noble piece of Architecture. The Quarto’s were separated from the Octavo’s by a pile of smaller vessels, which rose in a delightful Pyramid. The Octavo’s were bounded by Tea dishes of all shapes, colours and Sizes, which were so disposed on a wooden Frame, that they looked like one continued Pillar indented with the finest Strokes of Sculpture, and stained with the greatest Variety of Dyes. That Part of the Library which was designed for the reception of Plays and Pamphlets, and other loose Papers, was enclosed in a kind of square, consisting of one of the prettiest Grotesque Works that ever I saw, and was made up of Scaramouches, Lions, Monkies, Mandarines, Trees, Shells, and a thousand other off Figures in China Ware[…]. I was wondefully pleased with such a mixt kind of furniture, as seemed very suitable both to the Lady and the Scholar, and did not know at first whether I should fancy my self in a Grotto, or in a Library.

Quelle:Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

|

从中国开始放映电影到中华人民共和国成立的50多年时间中,美国电影迅速取代了欧洲电影在中国市场的垄断地位,好莱坞影片占中国年放映影片总量的80%以上,每年平均获得经济利润大约为600万美元。好莱坞电影对中国的政治、经济、文化和社会风尚产生了重要影响。中国政府、中国电影业和知识分子与好莱坞电影之间形成了复杂的冲突和依存关系。好莱坞在中国电影市场上的垄断地位直到1950年代以后才告一段落。而1990年代以后好莱坞在中国的重新进入,必将成为我们不能回避的政治、经济、文化现象。 关键词:中国电影史 好莱坞电影 电影经济 电影社会学 1896年电影首次在中国放映,距离卢米埃尔兄弟在巴黎首次公开放映电影还不到一年。从那以后的50年里,大量美国电影被贩运来中国分销到各地。在这50年中,中国各地影院上映的片目中,美国片占到了80~85%。作为20世纪中国的一道重要的文化景观,好莱坞对中国社会影响深远。早在30年代就有人说过,好莱坞已经“取代了传教士、教育家、炮舰、商人和英语文学,成为中国学习西方工业社会文化和生活方式的最为重要途径” 。的确,好莱坞的意义从来都不限于文化消费领域,它不仅通过票房收入和电影胶片、拍摄/放映设备的出口对中国经济产生了直接的冲击,同时,它还是促销美国产品的重要手段。美国商务部的一位官员曾明白指出,电影的影响使一些国家对美国商品的需求量增加了 。好莱坞称雄世界与美国经济利益在全球扩张之间的正比关系已经被许多学者的研究所证明。但是,到目前为止,还没有人对好莱坞在20世纪中国所起的作用做过深入系统的研究 。本文在大量原始资料的基础上,试图对中美两国在二十世纪前半期的电影姻缘做一个初步描述。它对基本史实的侧重和量化的研究方法可能会进一步激发学界对这一问题的兴趣,同时也为将来的深入研究奠定实证基础。 引言 鉴于美国电影在1950年前中国电影市场的绝对优势和霸主地位,研究中国电影史就不能不谈好莱坞。到目前为止,有关中国电影的研究比较集中在制片、甚至主要是创作方面,不仅电影经济学历来被忽视,而且与市场相关的发行与放映更是很少被关注。实际上,电影从来都不仅仅是一种艺术活动,而是一种经济活动。电影是通过市场进入社会的。研究电影就必须研究电影经济,研究电影经济就必须研究的有市场,研究电影市场就必须研究发行放映。对美国电影与中国的研究也同样如此。因此。我们的研究不妨被看作是一个纠偏的努力。即便从制片角度考虑问题,我们也不应忘记,中国本土电影的叙事策略、影像风格以及主题倾向,都在某种程度上是受到好莱坞的影响或者应对好莱坞的强势而发展出来的。因此,了解中国电影传统,必须理解好莱坞在中国的传播和影响。 过去几十年,有关美国电影的研究著述可谓汗牛充栋,但中外学者大都是从“内涵”而非“外延”的角度来研究好莱坞的。研究的重点都局限在好莱坞本身的发展史,各影像流派的兴衰,大导演大明星的创作生涯,以及这一切同美国大文化背景之间的关联。近年来,电影史家开始把眼光转向美国以外,从外延的层面上审视美国电影。正如电影史学家露丝•瓦西(Ruth Vasey)所指出的,由于好莱坞的海外市场收入多达其总收入的35%,美国制片人和编创人员从一开始就不能不顾及到美国以外的观众对他们的产品的反应。这样,不同国家、地区和文化的欣赏趣味和好恶取舍反过来也对美国电影的情节设计、人物塑造、影像风格及文化价值都有深刻影响 。换句话说,引入海外市场这一维度有助于更为充分地理解美国电影,并且将会矫正传统电影史中一贯只偏重电影制作而忽视发行、放映的倾向 。目前,这种全球视角的研究正方兴未艾。克蕾斯婷•汤普生(Kristin Thompson)、露丝•瓦西、托马斯H. 古拜克(Thomas H. Guback)和凯瑞•塞格瑞(Kerry Segrave)等人的开拓性研究勾勒了美国电影在全球市场中的发行情况;大卫•W•伊伍德(David W. Ellwood)、比尔•格兰瑟姆(Bill Grantham)、薇朵丽雅•格拉齐亚(Victoria de Grazia)、伊恩•贾维(Ian Jarvie)等人则微观地解剖了一些“案例”,具体研究了美国电影在特定地区或国家,如欧洲,南美,加拿大的发行情况。这些著作提供了某些启发,帮助本文深入研究好莱坞电影在中国的传播。 当然,本文中使用的“好莱坞”一词远不限于它的地理含义,而是意味着美国的电影工业。当19世纪末第一批美国电影在中国放映时,好莱坞还是一个偏僻小镇。只是到了20世纪20年代初,美国电影工业兼并整合,重新布局,并将制片系统搬到南加州之后,好莱坞才一跃成为电影城,并且成为整个美国电影业的象征。从这个意义上说,本文标题把1897年和好莱坞相提并论只是一种习惯性的使用而已。 好莱坞进入中国 在1895年12月28日卢米埃尔兄弟在巴黎的“盛大咖啡馆”首次公开放映记录短片不到一年之后,即1896年8月11日,电影这一发明就在上海徐园这一娱乐中心的游艺杂耍节目中被介绍给中国观众了。最先把电影引入中国的并不是美国人而是欧洲人,欧洲人对中国电影市场的统治地位一直持续到第一次世界大战爆发。 早在1899年,一个名叫加伦•白克(Galen Bocca)的西班牙人就开始在上海的几家茶馆、餐厅和娱乐中心放映电影。后来他把这些放映设备盘给了朋友安东尼奥•雷玛斯(Antonio Ramos)。雷玛斯是个商界高手,他很快就扩大了运营规模,还把电影放映从其它娱乐活动中独立出来。1908年他修建了可容250人的虹口大戏院,这是中国修建的第一座专门电影院。接下来,他又修建了更为精致的维多利亚影戏院,这是当时全中国最豪华的电影院。同时,英国人、法国人、意大利人、日本人、葡萄牙人,还有俄国人,都争着在中国电影市场中分得一杯羹。当雷玛斯将中国影戏院、万国、恩派亚等数家影院并入他的院线同时,一个名叫郝思倍(S. G. Hertzberg)的葡籍俄人则创建了爱普庐影戏院。还有早在1905年就已开始电影发行活动的意大利侨民恩里科•劳罗(Enrico Lauro),也改建了一家旧戏院,并将之命名为上海大戏院,放映电影 。这股建电影院的热潮不止局限在上海,也波及全国各地。美国驻汕头领事C. L.威廉斯(C. L. Williams)在1911年的一份报告中就曾提到,中国几乎每一个港口城市都以有一个电影院为荣,而很多口岸城市都有五、六个电影院之多。但是所有这些电影院都为欧洲人所掌控 。 欧洲人中又以法国人势力最大。虽然他们并没有大量介入影院、院线领域,但法国百代公司等却垄断了影片供应。从留声机到电影胶片,法国百代公司如同在整个亚洲一样,提供了对华的完整的链条业务,他们在加尔各答、孟买、香港、天津和上海都设有办事处。首映电影,每500米胶片,法国人的平均要价为500元 (民国旧币),相当于当时的211.5美元。第二轮片子租价则为400元,第三轮降为300元。电影租金要预先支付,由片主从租借人的押金中扣除。虽然美国人在亚洲也有负责租售其电影的代理处,设在菲律宾的马尼拉 。但当时在中国流行的美国电影,大部分也都是由法国人发行的二手货 。 美国电影在中国的出现应该是在1897年7月。新泽西州枫林市的詹姆士•里卡顿(James Ricalto)在上海天华茶园以及几处休闲公园放映了爱迪生的影片,当时里卡顿放映的短片非常受中国人欢迎,它们在天华茶园持续放映了10 个晚上,门票从铜钱10文到50文不等 。当时放映的影片包括《俄国皇帝游历法京巴里府》(《巴黎》)、《罗依弗拉地方长蛇跳舞》、《马铎尼铎(马德里)名都街市》、《西班牙跳舞》、《骑马大道》、《印度人执棍跳舞》、《骡马困难之状》、《和兰大女子笑柄》等等。有趣的是,这些最早的美国影片中,已经采纳了中国素材,其中的《罗依弗拉地方长蛇跳舞》是根据1889年巴黎博览会上中国丝带舞改编的。而本片的编舞洛依•福乐(Loie Fuller)也承认他是从中获得灵感的 。里卡顿的电影放映还导致了中国早期影评和电影报刊杂志业的诞生。到目前为止,已知最早的中文影评是《观美国影戏记》,发表于1897年9月5日的《游戏报》上。在文中,作者详细描述了他观看里卡顿的电影放映时的所见所闻。这是第一篇介绍美国电影的中文文章,其中关于里卡顿放映电影的资料信息极富价值: ……近有美国电光影戏,制同影灯,而奇妙幻化皆出人意料之外者。昨夕雨后新凉,偕友人往奇园观焉。座客既集,停灯开演,旋见现一影,两西女作跳舞状,黄发蓬蓬,憨态可掬;又一影,两西人作角抵戏;又一影,为俄国两公主双双对舞,旁有一人奏乐应之;又一影,一女子在盆中洗浴……又一影,一人灭烛就寝,为地瘪虫所扰,掀被而起捉得之,置于虎子中,状态令人发笑;又一影,一人变弄戏法,以巨毯盖一女子,及揭毯而女子不见;再一盖之,而女子仍在其中矣!种种诡异,不可名状。最奇且多者,莫如赛走自行车:一人自东而来,一人自西而来,迎头一碰,一人先跌于地,一人急往扶之,亦与俱跌。霎时无数自行车麕集,彼此相撞,一一皆跌,观者皆拍掌狂笑。忽跌者皆起,各乘其车而沓。又一为火车轮,电卷风驰,满屋震眩,如是数转,车轮乍停,车上坐客蜂拥而下,左右东西,分头各散,男女纷错,老少异状,不下数百人,观者方目给不暇,一瞬而灭。又一为法国演武,其校场之辽阔、兵将之众多、队伍之齐整、军容之严肃,令人凛凛生威。又一为美国之马路,电灯高烛,马车来往如游龙,道旁行人纷纷如织,观者至此几疑身入其中,无不眉为之飞,色为之舞。忽灯光一明,万象俱灭。其他尚多,不能悉记,洵奇观也!观毕,因叹曰,天地之间,千变万化,如蜃楼海市,与过影何以异?自电法既创,开古今未有之奇,泄造物无穷之秘。如影戏者,数万里在咫尺,不必求缩地之方,千百状而纷呈,何殊乎铸鼎之像,乍隐乍现,人生真梦幻泡影耳,皆可作如是观 。 从文中可知,这些影片显然有一部分是在美国制作的,比如《骑马大道》;而其他影片则可能来自欧洲。其中反映火车进站的片子估计就是卢米埃尔兄弟那部世界闻名的早期作品。显然,美国电影商人在中国的早期活动包括发行和放映欧洲影片。 初期,美国人在角逐中国电影市场的过程中落后于欧洲人。表面原因是由于租借或购买美国电影通常会比法国片贵,而且美国电影当时也不十分适合中国人的口味 。然而更深层的原因还是因为美国人早期并不十分热衷于投资中国市场。美国当时驻上海的副总领事纳尔逊•特鲁勒•詹森(Nelson Trusler Johnson)就说过:“美国电影在中国受欢迎应不成问题,但目前值不值得投资开辟这个市场,与那些更根深叶茂的竞争对手抢生意,却是另外一个问题。” 而且,在第一次世界大战以前,与在全球竞争中具有强劲资本优势的法国电影业相比,美国电影的产业规模还相当弱小。直到第一次世界大战切断了欧洲电影来源,并极大地削弱了欧洲人的主导地位,美国才有机会乘虚而入,后来居上。 美国人虽然在中国的放映和发行方面落后于欧洲,但在生产领域领却领先一步。1909年,美国人本杰门•布拉斯基(Benjamin Brodsky)就来到中国,创办了一家电影制片公司——中国电影公司,并计划以中国民间故事为题材,雇佣本土人才摄制发行电影。他用10万美元资金兴建了一个摄影棚、一个工作车间,在香港拍摄了《偷烧鸭》和《庄子试妻》。他曾在美国公映过几部他与中国摄影师Lum Chung*合作完成的电影 。布拉斯基虽非第一个来中国拍电影的外国人,但他的努力促进了中国早期电影制作的发展。首先,与其他多数外国电影生产商不同,他雇佣本土人才,参与其电影拍摄的中国人有机会学习制作电影的技能;其次,他的中国电影公司后来转给了另外两个美国人T. H.萨弗(T. H. Suffert)和A.依什尔(A.Yiesel),而他们最终又将公司委托给了中国人张石川(1890-1954)等人,这些人后来成为了中国电影工业的领袖。因此,如果提到中国最早的长片电影制作,我们就不不能不提到布拉斯基的中国电影公司 。 当然,中国最早尝试电影摄制要早于中国电影公司。1905年,任庆泰在北京的照相馆用胶片拍摄了由京剧名角谭鑫培主演的京剧《定军山》。但任庆泰的照相馆在一场神秘的大火之后关闭了。大部分发表于民国时期的关于中国早期电影的历史文献,都很少提到任庆泰和他对电影摄制的尝试,而一般都将中国电影摄制的开端追溯到布拉斯基的中国电影公司。后来中国电影史研究对任庆泰的重新发现、并将中国电影制作前溯到1905年,似乎与1949年后中国的民族主义意识不无关系 。 总之,从第一次世界大战在欧洲打响的时候开始,美国电影就开始全面进军中国市场,到战争结束时,好莱坞已经取代欧洲,后来居上。用一句美国外交官当时的话说,“现在中国上演的电影已经几乎全是美国片了。” 一项资料显示,美国出口到中国的胶片从1913年的189,740英尺(包括已摄制的胶片和没有曝光的原胶片)增加到1918年的323,454英尺。一战过后,到1925年则达到了5,912,656英尺(价值151,577美元)。这些数据表明,就在这段时期,美国对中国的输出总额从1913年的2100万美元剧增到1926年的9400万美元。而从比例上看,1913年美国对中国的电影出口额仅为美国出口总额的0.04%,而1925年就增加到了0.16% 。 从1921年开始,好莱坞的环球电影公司一马当先,其它公司也纷纷效仿,都在中国设立办事处推销电影。例如华纳兄弟在上海和天津设立了办事处,派拉蒙在香港、上海和天津设立了办事处。这些办事处与当地的审查官打交道,搜集有关中国电影市场的资料,将美国电影上映的情况反馈给纽约总部,监督中国影院执行合约,处理利润分成等。由于中国政府限制资金外流,好莱坞在中国的办事处也用赚来的钱从事投资房地产和股票 。 通常这些办事处的经理都是美国人或具有欧洲背景的人,但职员基本是中国人种,包括美国华裔和从美国回来的留学生。他们编写剧情摘要,电影翻译成中文。同时还在电影宣传、监督当地影院履约放映电影等方面发挥着重要作用。显然,他们对中美两种文化、语言的精通是好莱坞在中国成功的关键。实际上,中国观众对美国电影的体验是通过这一层中介实现的。正如刘禾在对跨文化交流的研究中所发现,翻译是这个过程中的关键环节,正是由于这一环节,异种文化才得以被消化理解 。某些美国电影的中文片名就很能说明翻译过程也即是重新阐释影片意义的过程。 1933年,电影《银锁》(The Silver Cord)(导演约翰•克伦威尔,John Cromwell)被引入中国。这部电影主要讲述了一个年轻人努力摆脱其母亲专制,追求独立的故事。很显然,这样的主题不符合中国传统所强调的孝顺观念。即使在叛逆精神很强的五四文学传统中,通常也只是攻击以父亲形象为代表的父权制度。而母亲形象一直都作为慈爱、无私的象征而被推崇。因此,如果这部电影不加以包装和处理其票房风险难以预测。为了解决潜在的文化冲突,雷电华(RKO)电影公司驻中国代表用了一句中国习语作这部影片的标题:“可怜天下父母心。”于是,这个母亲凡事大包大揽,对儿子生活横加干涉竟被化解为一种苦心孤诣,淡化了原电影的叛逆锋芒,使之与中国的道德准则更加接近。 在另一个例子中,环球电影公司的《后街》(导演约翰•M•斯塔尔,John M. Stahl,1932)发行时采用的中文片名是《芳华虚度》。电影原本讲述一个三角恋爱的故事,其中一名男子持续了长达30年的婚外恋。中文片名强调“虚度青春”,将观众的同情心引向女主角,并暗示了一种电影原本没有的道德判断 。虽然没有具体证据显示影片的不同中文译名是否导致票房收入上的差异,但这些例子足以说明这些办事处在中国观众接受美国电影过程中的重要性,并且表明他们在跨国文化传播中相当重视接受者的接受能动性。 好莱坞不仅在中国发行放映,而且也在中国拍摄制作电影。由于复杂的历史和文化原因,有关中国或以中国为主题的电影一直很受好莱坞制片人的青睐。到30年代这类影片的数目更是大幅度增加,各电影公司纷纷派剧组成员到中国来拍摄外景。其中最引人注目的是米高梅电影公司(MGM)来中国为《大地》(另译为《净土》,The Good Earth)(导演西德尼•弗兰克林,Sidney Franklin,1937)一片拍外景。这部影片是根据赛珍珠(Pearl Buck)获普利策奖同名小说改编而成。MGM 三易导演,历时四年,最终这部影片夺得了1937年的奥斯卡奖。其后,不少电影公司也投入到摄制中国片的热潮中。环球电影公司制作了《东方即西方》(East Is West)(导演蒙他•贝尔,Monta Bell,1930),派拉蒙公司制作了《上海快车》(Shanghai Express)(导演约瑟夫•冯•斯登堡,Josef von Sternberg,1932)和《将军死于黎明》(General Died at Dawn)(导演刘易斯•迈尔斯通,Lewis Milestone,1936),哥伦比亚电影公司(Columbia)发行了《颜将军之苦茶》(也译作《颜将军的伤心茶》,另译为《中国风云》,The Bitter Tea of General Yen)(导演弗兰克•卡普拉,Frank Capra, 1933),华纳兄弟制作了《中国煤油灯》(Oil for the Lamp of China)(导演莫文•莱罗依,Mervyn LeRoy,1935)和《上海西部》(West of Shanghai)(导演约翰•法瑞,John Farrow,1937)。这只是不完全的几个例子,此外还有无数以美国唐人街为背景拍摄的电影,以及“付满洲博士”(Dr. Fu Manchu)、查理•陈(Charlie Chan)系列电影。换一个角度来说,美国观众对中国片的兴趣也间接地推动了好莱坞向中国的扩张,而这一扩张既包括电影成品、胶片、器材的输出,也包括拍摄活动 。 需要指出的是,尽管故事片是本文的讨论重点,但它们只是好莱坞在中国经营的一小部分。根据1934年的一个调查,故事片只占到美国向中国出口电影的一半。而另一半是由短片、记录片和新闻影片构成的 。所以,这里的许多数据也包括故事长片以外的影片。此外,好莱坞不仅大量出口成品影片,还出口了大量的电影胶片和器材。中国的三大外国电影胶片提供商中有两个来自美国,分别是柯达公司(Kodak)和杜邦公司(Doupont)。另一个是德国的矮克发公司(Agfa)。从当时的报道中可以窥见他们之间的竞争非常激烈。柯达公司当时不惜花费巨资款待中国电影公司的主管人员,搞好关系 。1937年,当明星电影公司处于财政困境时,柯达和矮克发公司都表示希望通过购买该公司股票来承担该公司的债务 。同时,中国使用的音像器材多数也由美国制造商提供,其中西电公司(West Electric Company)和美国无线电公司(R.C.A.)是两大主要经销商,垄断了中国的音像器材市场 。在广州,美国西电公司将音像器材租赁给当地电影院,收取巨额租金。电影院要支付昂贵的器材维修费,经常不堪重负 。 美国的资本也在中国电影业中发挥了作用。曾经有人说中国电影业是唯一一个不依靠外资的行业,这一说法并不正确。和其它行业一样,中国电影业同样与外资分不开。但如果仅仅将美国资金流入中国看作是对本土电影行业的威胁,这也过于简单 。最新的研究显示,中国的制片商有时也会通过美国的华裔中介,运用美国资金为他们自己的利益服务。 好莱坞在中国的数据资料分析 尽管中外学者都承认好莱坞对中国影业的巨大影响,但至今为止,没有人对美国向中国输出的故事片的数目做过深入具体的调查。因为这项工作十分困难,需要大量的原始资料和长期积累,搜集本已不易,而搜集到的资料又常常零星分散,且往往互相矛盾,需要进行对比鉴别。我们通过大量的资料收集、分析、统计,获得了可能从来没有被公布的一些重要数据。尽管这些数据可能仍然并不完整和完全准确,但是却可能为将来的研究工作将提供必要的基础。 有关美国电影向中国出口的数目,20世纪20年代的估算主要是根据1926年孔雀公司(Peacock Motion Picture Corporation)董事长理查德•帕特森(Richard Patterson Jr.)的一个谈话。在那个谈话里,他提到1926年有450部外国电影在中国放映,其中90%是美国摄制的,即400部左右。而另一份材料显示,同年好莱坞八大公司的影片总产量是449部。按照这个数据,在中国放映的美国影片数量相当于八大公司年出品的90%左右 。 30年代的资料相对丰富一些。根据上海英租界公部局电影审查机构的统计,1930年在中国发行的美国电影不下540部 。而南京国民政府电影检查委员会在统计中称,1934年有412部外国电影在中国放映,其中有364部来自美国,占进口影片的88%。这个364的数字与好莱坞那一年生产的长故事片总数目基本一致。这个数字再次说明,从20到30年代,好莱坞出品的百分之八九十的影片都会在中国得到发行放映 。这个比例数字有很多旁证。1935年的一个资料就很说明问题: 1935年 在中国发行的电影数额 在美国生产的电影数额 米高梅 47 47 从上表可知,美国向中国输出的电影数额与好莱坞的年产量非常接近。在中国实际放映的美国电影总量还略多于好莱坞的年产量,这是由于一些旧片也在循环放映,例如表格中的“其他21部”就是如此。同样的规律也体现在1936年5月的一个数据资料中,上海当月放映的45部电影中有40部来自美国。根据这些资料可以推测美国向中国年输出电影总量在350到400左右 。 在1937年到1945年之间,因为爆发了抗日战争和太平洋战争,美国电影在中国的市场波动很大。所以,我们缺乏这一时期可靠而完整的数据。战后,美国电影卷土重来。根据电影史学家汪朝光的研究,战争结束后的1948年1月,上海放映了21部美国电影 。假设这个数据具有代表性,那么当年的美国电影在中国的发行量应该在252部左右,但这个数字实际上超过了好莱坞当年制作的电影数目总和 。形成这种情况的原因跟战争期间的影片积压有关。正是由于这个缘故,1946年有881部美国影片在中国上映,1947年393部,1949年142部。将这些数据同好莱坞在这相应四年里的确切产量相比,显然,40年代美国电影在中国的发行数目大大超过了美国本土电影的生产数目 。1949年美国电影发行数量因为中国内战和政局变化而明显下跌。 从目前掌握的数据来看,20世纪上半期,美国在中国平均每年发行电影在350部以上。1910和1920年代,发行量十分接近这个平均水平,但那时大部分是短片。30年代大部分年份的发行量跟这个平均数相当。但30年代的数据收集只包括长片,没有包括短片。1937年到1945年期间,由于中国正在进行抗日战争,数据显示美国出口到中国的电影数目在急剧下降。战后,美国输出电影的数目波动明显,从1946年的881部下降到1949年的142部。但是,和30年代一样,战后的影片发行数据没有包括短片和新闻影片。 在分析上述统计数据时,有几点因素需要考虑: 首先,这些数据都是从上海、天津和广州等大城市搜集得到。美国电影在中国的主要发行渠道集中在不到十个大城市。这些大城市构成了二次发行网络的中枢。从现在查阅的全国各地电影市场报告看,美国电影在大城市以外的地区放映很有限。即便偶尔有美国电影在内地放映,数量上也很有限,影响上也远不如国产电影大 。 其次,好莱坞每年向中国出口的影片量极其不稳定,并受到许多意外事件的影响。比如,它同中国片商频繁发生的冲突和对立,导致了电影院周期性地联合起来抵制美国电影。反过来,好莱坞有时也会切断对中国影院的电影供应,以抗议它在中国所遭遇到的所谓“不公平”待遇。此外,为了惩罚一些好莱坞制片厂拒不服从中国官方规定,或不按照要求删剪其影片,中国政府也经常采取拒检的办法,使其影片不能在中国发行。遇有这些情况,美国电影对中国的输出数量就会出现浮动。 第三,一些其它政治或自然环境因素也对影片进口发生影响,比如美日外交冲突,使好莱坞决定收缩它在远东地区的营业规模。另外,中国货币发生贬值,导致进口影片加价,好莱坞利润降低,也会削减它的输出量。1936年底美国船员罢工,大批货物、包括影片在港口滞留。有时,甚至恶劣的气候都会造成美国电影输出下降。因此,对美国电影输入中国的数量统计几乎不可能绝对精确 。 而计算好莱坞在中国所获得的利润则更难了。从社会环境看,20世纪前半叶的中国,战争频繁、社会动荡,带来许多市场变数,因此,很难找到具有典型性、能够反映整体情况的数据资料。从空间角度看,军阀割据和政治分裂使得不同地区的经济条件和税收政策差异很大。这反过来导致票房收入和电影发行费用上也有不同。除了向中央政府缴纳关税、进口税,外国电影发行商还要向地方政府机构交付各种费用。以上海为例,光是电影审查机构就有三个,法租界,英租界,还有国民党政府,都对电影施行检查,并收取审查费。从时间角度看,中国政府对外国电影在不同时期都采用了不同的税收政策。例如,在20年代外国电影无需交纳审查费用,但1931年以后必须支付每500英尺胶片20元的电检费。同样,外国进口电影的关税也从20年代的5% 增加到30年代的10%,这还不包括国家和地方政府征收的娱乐税。 30年代后期,美国驻华大使克莱伦斯•高思(Clarence Gauss)抗议中国海关压制代表好莱坞八大制片厂利益的中国电影贸易商会(The Board of Film Trade),征收“二次进口税”。在他写给海关的抗议信中,高思引证了这八大制片厂提供的陈述材料,以说明好莱坞在中国的利润很低,不应该征收二次征税: 按照电影发行商的阐述,如果考虑到关税和其他费用如租金、发行费等的总开销,我们不难理解,即便能够盈利,最后所得的利润也是微乎其微的。他们还认为此刻并没有到缴纳更多关税的地步,特别是当前的对抗导致了他们的生意在急剧萎缩 。 米高梅电影公司在为高思准备的材料里提到几个具体例子。其中之一是一部叫做《石榴裙下》(Petticoat Fever)(导演乔治•费兹里斯,George Fitzmaurice,1936)的电影。本片于1936年4月25日从纽约运到中国,在31个地区放映,进账8483.85美元,其中791.83美元用于向中国缴纳关税,占到了公司利润的10%。再除去其他费用,包括交给电影制造商的租赁费、宣传费、检查费、保险费、海运费、发行费、保护费和库存费,公司最后所得的利润微乎其微。哥伦比亚公司的例子是电影《人言可畏》(The Whole Town’s Talking)(导演约翰•福特,John Ford,1935),放映35轮,进账5400.00美元,其中539.54美元或者说总收入的10%作了进口税。雷电华公司的《午夜之星》(Star of Midnight)(导演斯蒂芬•罗波特,Stephen Roberts,1935),放映27轮,进账6517.95美元,其中778.43美元上缴关税。派拉蒙公司的《黄粱一梦》Thirty Day Princess(导演马里恩•格林,Marion Gering,1934),进账9373美元,向中国上缴738.62美元关税。最后,环球公司的《安第斯山风暴》(Storm over the Andes)(导演克里斯蒂•卡巴纳,Christy Cabanne,1935)进账6407.36美元,华纳兄弟公司的《敞篷餐厅》(Ceiling Zero)(导演霍华德•霍克斯,Howard Hawks,1936)进账6443美元,两个公司都缴纳了占到收入10%的税收。当然,这些数据是八大公司为证明他们在中国牟利甚微、抗议强加在他们身上的税收而准备的,因此,这里的盈利估算可能是极端保守的。如果以这里的数据作基础,平均每部影片净盈利大约在8000美元。再把这个数字乘以年均进口量的350或400部,那么好莱坞每年从影片出口一项就从中国获得利润280万到320万美元。 当时的国民政府中央电影检查委员会的主任罗刚则估计,好莱坞在中国所获利润每年应该达到1000万美元 。其它还有许多数据往往介于这两个估价之间。例如,当时的中国海关估计美国电影发行商获取的纯利润为每部影片1200到30000美元之间,即平均每部15,000美元,这是好莱坞制片公司驻华代表所提供的数据的两倍 。根据上述数据,如果采用中美双方数字的简单平均数,好莱坞在中国的利润大概为每年600万美元左右。而一份20年代的数据显示,从1915年前后到20年代中期这10年,美国电影平均利润每年超过700万美元,这与每年600万美元的估计大致相近 。同时,这个估计也与1935年一份资料反映的情况一致。这份资料显示,好莱坞的中国销售代表从1934年的利润中拿出100万美元汇回美国 。而我们知道,按照民国政府的政策限定,外商的外汇外流额不得超过其总利润的15% 。这也就是说,100万美元反映了好莱坞至少有660万美元的总收入。这既对应了海关的估算,也与20年代的数据吻合,同时还与战后以及50年代初的统计资料基本一致 ,因此应该是相对恰当的数字。 美国影业行内人士也有一个估计认为,好莱坞通过海外发行和租赁,平均每年有8~9亿美元的收入。而中国在这个总收入中所占份额为1%,即每年800~900万美元 。中国电影史学家汪朝光的研究表明,从1945年到1950年期间,好莱坞每年单从上海获取的利润就有270万美元 。由于上海是美国电影在中国的最重要市场,并且它的票房收入占到全国总额的35~50%,通过上海的票房收入可以计算出全国的票房收入应在每年540万到770万美元之间。考虑到一些市场波动和边际误差,所有这些数据都一致表明好莱坞在中国的平均年收入为600到700万美元。除非进一步的研究提供新的发现,这应当是从经济学维度评估好莱坞在中国的比较可靠的依据。 好莱坞在中国市场所面临的冲突 好莱坞进入中国市场,一直都面临各种来自市场内部的、来自政府的、来自社会的冲突。在这种冲突中,好莱坞积累了一系列处理危机、维护和扩大市场的机制和经验。 好莱坞与中国电影市场的冲突首先是与中国影院业的冲突。好莱坞在中国市场的回收主要是通过两种途径实现的,即分账制和包账制。分账是将票房收入由影院方面和发行方面按一定比例分享。而包账是由影院方面事先买断影片的版权和发行权。这样做的好处是院方在买断以后可以独享影片的全部利润。由于复杂的原因,抗战胜利以前好莱坞在中国一直没有介入影院经营。虽然米高梅公司曾经计划在上海建立影院,专门放映该公司的影片,但这一计划一直未能付诸实现。直到抗战胜利后,米高梅公司才在上海收购了大华电影院,使之成为中国第一家美属电影院。因而,通常美国电影发行商都是将他们的电影租给中国的影院老板,并跟他们分享票房收入。 好莱坞在票房收入上所占的百分比份额随着影院的不同而有差异,随着时间的变动而上下波动,这在很大程度上受市场供需制约。在多数情况下,票房收入分成在30%到70%之间。通常好莱坞各制片厂都跟特定的一家或多家影院每年签订一个合同。在合同期内,制片厂向影院提供一定数量的电影。而影院方面则有义务为这些影片安排足够的放映时间,一般是3到5天,但如果一部电影的上座率超过45%,影院则延长其放映时间。至于公关宣传和作广告费用则由影院负担。如果使用由制片方面提供的电影预告材料和海报等物资,影院还需另交租金 。由于条件苛刻,放映商宁愿一次性买断版权和发行权,以摆脱好莱坞的制约。所以,他们一旦有可能就会想办法摆脱分帐式协定 。 而从好莱坞的角度出发,分帐制使他们得以更方便地控制影院,在电影放映的类型、市场营销中的包装方式,以及分配给每部电影的放映时间等方面都掌握着主动。特别是他们的捆绑销售(block booking)更是采用“或者全部或者全无”的方式“欺负”放映商。正是由于这个原因,好莱坞很少选择包帐的运营方式。在少数情况下,中国影院方也曾买到版权和发行权,但一般是从好莱坞以外的独立电影制片人那里买到的。例如在1936年,一家中国影院的老板何挺然就花25000美元买断了查理•卓别林的电影《摩登时代》的发行权 。 总之,一方面好莱坞要依赖中国的放映商来实现其利润,另一方面中国放映商也靠好莱坞的片源作为生存的保障。这种双向依赖每每在冲突和对立中表现得越发突出。1936年,中华民国政府中央电影检查委员会决定,提高外国电影的审查费用。好莱坞向中国政府提出抗议,但无济于事。于是他们让影院主来分担费用。遭到后者拒绝后,好莱坞对中国实行影片禁运。僵局持续了4个月,双方都损失惨重。最终,好莱坞和中国影院方面达成妥协,分摊这部分新增的审查费用 。 好莱坞意识到,要维持其在中国的统治地位,各大制片厂必须加强协作。自从环球影业公司率先于1921年在上海创立办事处后,其他制片厂也相继在中国各大主要城市创办事务所或者雇佣销售/发行代表。随着业务上的开展,各公司都感觉到彼此间有协调行动的必要。于是成立了诸如美国片商协会(The American Film Exchange in China)、美商电影公会(The Film Board of Trade)等组织。一旦中国放映商不遵守与某一制片厂签订的“游戏规则”,其他制片厂也会联合拒绝向其提供电影,迫使影院方面对违约行为要慎之又慎。美商电影公会规定了电影的放映安排程序、每部电影的放映时日,有时甚至还规定电影票价 。为了保证这种控制,好莱坞也担心中国放映商之间结盟。抗战胜利后,国民政府将电影业大部作为敌产收归国有,政府控制下新成立的中央电影股份有限公司成为中国最大的电影供应商,并介入影片发行,同各影院签订协约。他们的做法对好莱坞的市场垄断构成了直接威胁。美国在华电影发行商向他们的纽约老板发电报,要求总部停止与中电交易。纽约方面也答应不与中电式的垄断集团继续交易 。 发行商和放映商都在追逐利润的最大化。所以只要有更大的赢利机会,发行商和放映商都会改变协议。1939年,根据沪光大戏院同米高梅公司签订的合约,这个二轮影院每年要放映一定数量的米高梅公司出产的电影。但这一年,该影院很幸运地获得中国热门电影《木兰从军》的放映权,这部电影在上海引起了轰动效应,并且因为持续满场,影院破例放映了一个多月。在这种情况下,沪光几乎毫不犹豫地就撤销了原放映计划中排给米高梅的电影,即便会引起纠纷也在所不惜。米高梅后来果然将沪光告上法庭,并向影院索赔6万元补偿金 。 尽管有这类矛盾,中国影院业仍然是好莱坞最重要的同盟。而中国的电影制作业却对好莱坞恨之入骨,因为它夺走了国产电影的观众,瓜分了电影市场并截取了中国制作商的利润。中国电影制作业的头面人物经常以民族主义的旗号猛烈抨击好莱坞,并同文化精英和政府联合,结成抵制好莱坞的联盟,以期弱化和动摇美国电影在中国的统治地位。正是他们或明或暗的策动和支持,美国人几次试图收购中国的一些电影厂和影院都未成功 。 如果说中国电影制作业反对好莱坞具有明显的经济利益动机,那么文化精英和政府官员对美国电影的敌意则主要是出于文化和政治动机。美国人的价值观和行为规范对20世纪中国人的影响已经潜移默化,深入到社会生活的各个方面。20世纪30年代,中国电影女演员黎灼灼同男朋友张翼分手,公开报道的原因就是认为张没有“白人”的浪漫 。这说明一种新的恋爱观和性道德准则已经在中国获得相当广泛的接受,否则她不可能这样来为其行为辩护。而美国电影在传播这些道德观和行为方式的过程中则起到了关键性的作用。在另外一个类似例子里,上海一个提供陪伴服务的公司在其广告中宣称,他们的姑娘既有梅蕙丝型的(Mae West,30年代性感明星)、也有珍•哈露型的(Jean Harlow,当时的美艳巨星)、还有克莱拉•宝(Clara Bow)这样的类型 。显然这些美国明星已成为大众心目中的女性偶像了,因为广告策划者已经假想读者都一定熟悉这些好莱坞影星的形体面貌。其实不光是女性美,中国人对于男性美的观念也被好莱坞重新塑造了。一本女性杂志发起的一个读者调查显示,最受其女性读者渴望的男人品质有二:健美和浪漫 。显然,这两者都不是中国传统社会里女性选择丈夫的最重要标准。现代中国妇女把这两点作为判断男性可爱与否与好莱坞的银幕形象影响显然有很大关系。正是针对好莱坞的这种文化价值观渗透,中国文化精英频频向当局人士呼吁,要对美国电影采取严格的限制措施 。美国电影中包含的个人主义价值观、个人自由、享乐主义态度与中国主流文化传统显然是相冲突的,甚至很容易成为中国主流文化的攻击目标 。 虽然当时的中国政府也同意这些文化精英的观点,认为好莱坞具有对中国传统道德结构的瓦解作用,但它的当务之急是限制好莱坞对中国造成的经济和政治上的损害。在经济层面,政府希望保护国产电影工业,使其能够在美国电影的阴影下存活并发展,并减少资产外流。在政治层面,国民党官方对美国电影里的辱华镜头和对话甚为反感。从某种意义上说,南京政权下的电影审查的起源与1930年那场抗议罗克(Harold Lloyd)辱华电影《不怕死》(Welcome Danger)的风潮有很大关系 。取缔《不怕死》主要是由国民党上海特别市政府在背后推波助澜,接下来则是中央政府行使职权,禁止辱华电影在中国上映。政府的电影检查委员会(National Film Censorship Committee)成立伊始就拿环球公司的《东方即西方》(East Is West)开刀。当时,中国驻芝加哥的外交官致函电检会,提醒国内电影审查人员注意该片的辱华性质。当影片报送南京审查时,电影检查委员会便未予通过,并禁止这部电影在中国放映。后来,环球公司删除了被认为有侮辱性质的场景和对话,才获发行放映许可 。类似的例子还有《上海快车》、《颜将军之苦茶》和《将军死与黎明》。因为《将军死与黎明》一片,派拉蒙公司在中国还遭到了全面禁映,直到公司屈服于中国审查人员的要求,不再发行该电影以后禁令才解除 。 但与此同时,国民党政府也期望同美国保持友好关系,希望获得美国在经济和政治上的支持。处于外交考虑,政府并没有对好莱坞采取激烈措施。也正因为如此,每当好莱坞在中国遇到麻烦时,美国政府都会出面帮助解决争端,以维护美国电影业的利益。而国民党政府多数情况下也会采取妥协立场。但战后中国的电影行业敦促政府采取保护性政策的呼声日益强烈,政府方面也被迫开始考虑采取一定程度的限制好莱坞的政策。但随着蒋介石政权的瓦解,国民政府的对外电影政策的面貌已经无从猜测了 。 好莱坞在中国的历史性断裂 1949年,随着国民党政权的瓦解,好莱坞在中国的帝国时代也结束了。尽管中国共产党没有立即在各大城市停映美国电影,但要求美国电影发行商自行审查,并禁止放映不利于新政权的电影。这意味着在中国放映的美国电影中不能有反苏、反共和夸耀美国军力的任何内容 。实际上,中共政权在1950年夏天以前并未放弃与美国改善关系的希望,所以也不愿因为与好莱坞对抗而使中美外交复杂化。当时的新闻媒体对于好莱坞电影的批评也比较温和,而且这些批评也往往并非来自政府的指示 。 但1950年6月朝鲜战争爆发后,中美关系急剧恶化,中共政府迅速调整了对美立场,包括开始施行制约好莱坞的政策。1950年7月,中央文化部发布《国外影片输入》、《电影新片领发上演执照》等五项有关电影的暂行办法,目的之一便是削弱好莱坞在中国的支配地位 。到1950年秋,批判美国文化、特别是美国电影的社论和文章几乎铺天盖地。这些文章或强调美国电影工业为华尔街的资本家所操控,或抨击好莱坞不惜牺牲艺术来迎合低级趣味,揭露好莱坞如何与美帝国主义沆瀣一气对中国实行经济盘剥。 从批判的内容来说,这时对好莱坞的批判与1949年以前似乎是一脉相承的,但批判方式却大不相同。国民党时期对好莱坞的批判仅限于知识分子精英圈子,而中国共产党领导下的批判则成为了轰轰烈烈的群众运动。政府有效地将观影活动政治化,从而成功地创造了一种社会氛围,将观看美国电影视为消极颓废、不思进取和缺乏爱国心的表现。这一切都体现了共产党后来执行文化政策的一种方式。 1950年前后,报刊杂志刊载了大量好莱坞影迷的忏悔录,纷纷指证美国电影对中国人民造成的伤害和损失。这些“忏悔”用个人经验来证明美国电影如何导致了精神蜕化。一篇名为《好莱坞电影看坏了好人》的文章讲述了一个叫吴正明的高中生沦为罪犯的故事。这篇文章说,吴迷恋美国电影,为模仿银幕上的英雄,他打扮得像一个牛仔,并效仿电影里的方式跟女孩调情,走向堕落 。在另一篇文章里,一个女影迷承认,每次看完美国电影,她都感到沮丧,因为银幕上的一切对她来说都不可企及,令她强烈感觉到生活的欠缺 。还有一个家庭妇女指责美国电影破坏了她的家庭。据她说,她以前的生活快乐和充实,但看了过多的美国电影后,感到银幕上的男人形象令自己的丈夫相形见绌,于是沉迷于美国人的生活方式之中,在服装、室内装饰和家具上奢侈消费,大大超出了她的经济能力。最后,她的丈夫由于不能忍受她不断的挑剔和唠叨而跟她离婚了 。 正是在在全国声讨好莱坞的浪潮下,许多电影院职工及其工会要求停映美国电影。迫于这种压力,在上海拥有米高梅公司电影独家发行权的首轮影院——大华影院,于1950年10月17日静悄悄地决定停映美国电影。巴黎影院几周后也采取了相同的但更大张旗鼓的行动。11月10日,他们的职工挂出了一条横幅,上面写着:“拒映美片。”职工们要求院方支持他们的行动,并且鼓动其他影院的同行采取类似行动。在他们带动下,确有几家电影院参与了这一联合抵制活动,但这些电影院大多是二轮影院,主要放映国产影片,所以他们的行动象征意义多于实际意义。但客观上起到了推波助澜的效果。由于越来越多的电影院或迫于政治压力,或基于爱国热情而加入联合抵制,代表40多家电影院的上海电影院同业公会在11月11日召开了紧急会议,决定属下所有的电影院停映美国电影。于是,好莱坞在中国几十年的历史终于告一段落 。 美国电影虽然停映了,但舆论声讨还在持续。新闻报纸和社论专栏中的批判文章和个人见证比比皆是。到1951年,还陆续出版了一些批判文章汇集,对好莱坞予以更为系统和详尽的批判。有一本集子的编者明确地说: 美帝国主义的电影,这一支侵略的队伍,在中国大陆上我们已经把它基本上歼灭了。可是在这个战场上,它用的是最恶毒的细菌武器,所以在敌人败溃之后,我们还要好好检查一下,有没有细菌藏在看不见的地方。要用显微镜照一照,都是什么样的细菌。 显然,禁映美国电影还只是开始,更重要的是还要随着中国进行的“社会主义改造”,中国还要彻底消除好莱坞“流毒”。 不过,尽管当时的主流舆论都只有一种“反美”声音,但一些美国电影的忠实影迷还是纷纷致信报社编辑,反对禁映好莱坞电影。有一封读者来信对禁映美片有理有据地提出了三点质疑:首先,如果排斥美国电影是基于它们造成的经济剥削,那么这一理由已经不再成立,因为1949年以后美国电影在中国的发行已经控制在中国发行商或放映商的手心,并且产生的利润也留在国内了。其次,并非所有的美国电影都像被指控的那样低劣。一些电影,比如《一曲难忘》(A Song to Remember)(导演查尔斯•维多,Charles Vidor, 1945),就具有较高的教育意义和艺术价值。因此,将所有美国电影全部取缔并不合理。第三,美国电影工业作为一个整体可能是被资本家操纵,为美帝国主义服务,但在好莱坞工作的大部分导演、编剧、演员和制片厂其他的工作人员都是正派的、爱好和平的,不分青红皂白地拒绝所有美国电影,对这些人是不公平的 。虽然类似这样的意见往往被汹涌澎湃的讨伐洪流所淹没,但这封信只是冰山一角,众多好莱坞影迷对这场运动还是感到不满。具有历史意味的是,大约50年以后,正担任中国共产党总书记的****在一次答记者问时也公开谈到,他40年代曾是好莱坞迷,当时看过的许多影片仍记忆犹新。他特别提到的一部电影便是《一曲难忘》。这也说明了好莱坞在中国经久不衰的影响力,也让人对1950年那场轰轰烈烈的抵制好莱坞运动的历史根源产生了更多的思考。 实际上,尽管在其后30年里,普通中国观众再也看不到美国电影了,但好莱坞并没有完全从中国销声匿迹。从50年代直到80年代初期,政府官员、学者以及电影摄制人员还是能够经常看到美国电影 。50年代开始电影生涯的女演员向梅曾在回忆中提到,她最喜欢的美国电影之一是《罗马假日》(Roman Holiday)(导演廉姆•华尔,William Wyler, 1953),并看过不下三遍 。这部电影完成于1953年,那时,好莱坞影片已经不能在中国公开放映了,但显然,像向梅这样的电影圈内人士还是能看到美国电影,而且还能够重复观看。这表明美国电影仍然在小范围内放映。此外,有关好莱坞的新闻报道和研究文章仍不时出现在公开刊物上。在这个意义上,美国电影并没有完全从大众的记忆中消失。 文化大革命的后期,特别是80年代后期,好莱坞开始逐渐在中国东山再起。《星球大战》、《超人》等科幻电影进入中国。特别是1994年开始,中国允许引进国外所谓“大片”分帐发行,尽管受到配额限制,但是,好莱坞的主流商业影片开始在中国大规模上映。若干好莱坞制片厂都恢复了在中国的办事处,等待时机卷土重来。随着中国加入世贸组织和来自好莱坞的压力,中国政府将进口影片的配额逐年增加,从10部增加到50部,这些进口影片占据了中国电影50%以上的市场份额。此外,美国电影的DVD光碟、特别是盗版光碟在中国也非常流行,加上电视台播放的好莱坞影片,这些都使好莱坞电影在中国形成了新的经济和文化现象。而如何面对好莱坞的进入,对于正在复苏的中国电影、正在改革的中国文化产业经济、正在重建的中国文化和正在转型的的中国政治,都是一种考验。而20世纪前半期的历史经验则为我们回应这种考验提供了历史的参照。 (尹鸿 萧志伟 来源:《世纪中国》 ) |

1 Acknowledgements: The author wishes to thank the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, London, for providing support for work on this article through the grant of a postdoctoral fellowship.

See Jennifer Chen, Julie Emerson and Mimi Gates, eds., Porcelain Stories: From China to Europe (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000) ; John Ayers, et al., Porcelain for Palaces: the Fashion for Japan in Europe 1650-1750 (London: Oriental Ceramic Society, 2001) For a history of the imports and collections of Chinese porcelain see chapter 1 of Stacey Pierson, Collectors, Collections and Museums: The Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560-1960, (Bern: Peter Lang, 2007).

2 Oliver Impey, “Japanese Export Porcelain”, in Porcelain for Palaces, 25-35.

3 Rose Kerr, “Missionary Reports on the Production of Porcelain in China”, Oriental Art, 47. 5 (2001): 36-37.

4 For a definition of these terms, see Krzysztof Pomian, Collectionneurs, amateurs et curieux, Paris, Venise : xvie-xviiie siècle, Paris, Gallimard, 1987.

5 Anna Somers Cocks, “The Nonfunctional Use of Ceramics in the English Country House During the Eighteenth Century”, in Gervase Jackson-Stops, et al., The Fashioning and Functioning of the British Country House, Studies in the History of Art 25 (New Haven: Yale UP. 1989).

6 The collection bore the name “the Museum Tradescantium or a Collection of Rarities Preserved at South Lambert neer London by John Tradescant of London”. Cited in Douglas Rigby, and Elizabeth Rigby, Lock, Stock, and Barrel: the story of collecting (London: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1944), 234.

7 Mercure Galant (juillet 1678), cited in Hélène Belevitch-Stankevitch, Le Goût chinois en France. 1910. (Genève: Slatkine, 1970), 149.

8 See John Ayers in Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, eds., The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Clarendon, 1985), 256-266 and Oliver Impey, “Collecting Oriental Porcelain in Britain in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries”, in The Burghley Porcelains, an Exhibition from the Burghley House Collection and Based on the 1688 Inventory and 1690 Devonshire Schedule (New York: Japan Society 1990), 36-43.

9 See Pierson 31-33.

10 See Oliver Impey, “Porcelain for Palaces”, in Porcelain for Palaces, 56-69.

11 Cited in Joan Wilson, “A Phenomenon of Taste: the Chinaware of Queen Mary II” Apollo 126 (August 1972): 122. For the decoration of Kensington Palace, see Rosenfeld Shulsky, “The Arrangement of the Porcelain and Delftware Collection of Queen Mary in Kensington Palace,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 8 (1990): 51-74; T.H. Lunsingh Scheurleer, “Documents on the Furnishing of Kensington House,” Walpole Society 38 (1960-1962): 15-58, and Oliver Impey and Johanna Marshner, “ʽChina Mania’: A Reconstruction of Queen Mary II’s Display of East Asian Artefacts in Kensington Palace in 1693”, Orientations (November 1998).

12 For more information on the arrangement of porcelain in these rooms, see Robert J. Charleston, “Porcelain as a Room Decoration in Eighteenth-Century England,” Magazine Antiques 96 (1969): 894- 96.

13 Impey, and Ayers, Porcelain for Palaces, 56-57.

14 Hilary Young, English Porcelain, 1745-1795: its Makers, Design, Marketing and Consumption. (London: Victoria and Albert Publications, 1999), 167-69.

15 See Tessa Murdoch, Noble Households. Eighteenth century inventories of great English houses, (Cambridge: John Adamson, 2006).

16 For studies on chinoiserie, see Hugh Honour, Chinoiserie: the Vision of Cathay (London, 1961); Oliver Impey, Chinoiserie: the Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration (London, 1977); Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding, “Dragons, clochettes, pagodes et mandarins: Influence et representation de la Chine dans la culture britannique du dix-huitième siècle (1685-1798)”, unpublished PhD thesis, Université Paris 7 Denis Diderot, Paris, 2006 ; David Porter, The Chinese Taste in England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

17 Collett-White 48.

18 The poem depicts the drowning of Walpole’s cat Selima while attempting to catch a goldfish in the porcelain tub. For a study of Walpole’s ceramic collection, see Timothy Wilson, “ʽPlaythings Still?’ Horace Walpole as a Collector of Ceramics,” in Michael Snodin and Cynthia Roman, eds., Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill (New Haven, CT: Yale U.P, 2009).

19 For more information on Beckford’s collections, see Derek Ostergard, ed., William Beckford, 1760-1844: An Eye for the Magnificent (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001).

20 See Craig Clunas, ed., Chinese Export Art and Design (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1987).

21 John Stalker and George Parker, Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing Being a Complete Discovery of these Arts. (Oxford, 1688), Preface.

22 Sigmund Freud, “Fetishism,” in Adam Phillips, ed., Sigmund Freud: the Penguin Reader, (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 91-93.

23 The World n°38 (20 September 1753).

24 I draw here upon William Pietz’s anthropological study of the history and origin of the term “fetish”. See his articles on the subject, “The Problem of the Fetish, I,” Res 9 (Spring 1985), and “The Problem of the Fetish, II: the Origin of the Fetish,” Res 13 (Spring 1987).

25 The World No. 38 (20 September 1753).

26 See Chapter 3 in David Porter’s The Chinese Taste in England, 57- 93.

27 Catherine Lahaussois uses the expression “broderies de porcelaine” in Antoinette Hallé, De l’immense au minuscule. La virtuosité en céramique, (Paris : Paris musées, 2005) 48.

28 For a study of the Duchess of Portland’s passion for conchology, see Beth Fowkes Tobin, “The Duchess's Shells: Natural History Collecting, Gender, and Scientific Practice”, in Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin, eds., Material Women, 1750-1950 (London: Ashgate, 2009), 301-325.

29 See Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace, Consuming Subjects: Women, Shopping, and Business in the 18th Century (New York: Columbia UP, 1997) 20-29; David Porter, “Monstrous Beauty: Eighteenth-Century Fashion and the Aesthetics of the Chinese Taste.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 35.3 (2002): 395-411.Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding, “Frailty, thy Name is China: Women, Chinoiserie and the threat of low culture in 18th-century England”, Women’s History Review, 18.4 (Sept 2009): 659-668; Stacey Sloboda, “Porcelain Bodies: Gender, Acquisitiveness and Taste in 18th-century England”, in John Potvin and Alla Myzelev, eds., Material Cultures, 1740-1920 (London, 2009), 1-36.

30 William Park. The Idea of Rococo (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1993), 75-77.

31 See chapter 4 in Parker’s The Idea of Rococo, 96-106. For a study of history of the rococo and its presence in English decorative arts, see Michael Snodin ed., Rococo Art and Design in Hogarth’s England (London: V&A Publication1984) and Charles Hind, ed., The Rococo in England. A symposium (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1986).

32 The Spectator no. 37, 12 April 1712.

33 Ibid.

34 “The senses at first let in particular ideas, and furnish the yet empty cabinet, and the mind by degrees growing familiar with some of them, they are lodged in the memory, and names got to them.” John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) Book II, Chapter II, section 15.

35 Alain Bony, Léonora, Lydia et les autres : Etudes sur le (nouveau) roman (Lyon: PUL, 2004), 9-12.

36 Claude Lévi-Strauss, Le Cru et le cuit, (Paris : Plon, 1978).

37 Batty Langley, Practical Geometry, (1726), 101.

38 The World No. 38 (20 September 1753).

39 For a study of the sensualist aesthetic of chinoiserie, see Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding, “De l’exotisme au sensualisme: réflexion sur l’esthétique de la chinoiserie dans l’Angleterre du XVIIIe siècle”, in Georges Brunel ed., Pagodes et Dragons: exotisme et fantaisie dans l’Europe rococo (Paris Musées: Paris, 2007), 35-41.

40 Philippe Minguet, L’Esthétique du rococo. (Paris : Vrin, 1966).

41 See Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding, “Dragons, clochettes, pagodes et mandarins”, 103-119.

Several meanings can be ascribed to the presence of porcelain in English interior decoration. Oriental porcelain can be construed, I suggest, as a memento for men and a fetish for women. Porcelain was the material emblem of long-distance travels, and more symbolically, of what was perceived as commercial successes resulting from the Anglo-Chinese trade. Porcelain acted as a narrative object that visually told a story. Numerous export porcelain plates and dishes represented East India Company vessels moored in Canton or sailing along the Chinese coast, or imaginary Chinese landscapes and everyday scenes that provided the basis for chinoiserie design used by European porcelain factories for the decoration of their wares.20 English ceramic makers also decorated their vessels with images based on illustrations from travel books, such as Johan Nieuhof’s famous 1673 Embassy from the East India Company. Analogous to sea-narratives and travel books which were highly popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, the iconography on oriental porcelain traced one episode of an imaginary journey to China or Japan while porcelain itself was the tangible evidence of an actual journey to Canton. By viewing oriental porcelain, or by gazing at images of China or at chinoiserie vignettes, the viewer was reminded of the commercial voyages that had been undertaken to acquire these commodities, while he could slip into the role of traveller and explorer and let his imagination wander along the distant shores of the Far East, the “Terra incognita and undiscovered provinces” mentioned by Parker and Stalker in their 1688 Treatise on Japanning and Varnishing21. Porcelain wares functioned as mementoes of the (East India Company’s) commercial endeavours that had been necessary to bring these commodities back to England. A Chinese porcelain sauceboat in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, decorated with two cartouches depicting English ships departing Plymouth in the background (a floating English flag planted on the ground identifies the English coast) and arriving in the Pearl River in the foreground (a pagoda and a typical Chinese rock identify the Chinese coast) is one of numerous examples of how designs worked as travel-narratives (figure 1). The distance between the English coast and the Chinese one, rendered by the use of perspective in the scene, acquires a temporal dimension as it stands for the actual duration of the voyage and that of the written narrative. If not all men were merchants who had actually gone to China, they could picture themselves as potential merchants or adventurers and explorers. Porcelain could appeal to merchants’ dreams of exploration and wealth, but also appealed to the scientific and exploratory nature of the connoisseur and virtuoso.

If the function of porcelain as travel narrative played the role of a memento for male audiences, it played the role, I argue, of a fetish for female audiences. Freudian interpretation of the fetish underlines the role of the fetish as a marker of an absence or a lack.22 By invoking this lack, the fetish also disavows it and makes the absent object present. In William Burnaby’s The Ladies’ Visiting Day dated 1701, the female character Lady Lovetoy laments over a lack, namely the impossibility for women to travel to the East. The purchase of exotic goods is presented as a replacement of voyages to China:

Fulvia: I wonder your Ladyship, that has such a Passion for those Parts of the World, never had the Curiosity to see ‘em.

Lady Lovetoy: Alas! The Men have usurp’d all the Pleasures of Life, and made it not so decent for our Sex to Travel; but I manage it as Mahomet wou’d ha’ done his Mountain […] Every Morning the pretty Things of all these Countries are brought me, and I’m in love with every Thing I see.

Quelle:Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.