我的频道 - Kulturaustausch Ost-West|东西方文化交流|East-West cultural exchange|Échange culturel Est-Ouest

France was one of the most energetic and creative nations in Western history. The ever-evolving French clothing tradition has remained an inspiration for fashionistas, says Abarrna Devi R.

Fashion is an integral part of the society and culture in France and acts as one of the core brand images for the country. Haute couture and pret-a-porter have French origins. France has produced many renowned designers and French designs have been dominating the fashion world since the 15th century. The French fashion industry has cultivated its reputation in style and innovation and remained an important cultural export for over four centuries. Designers like Gabrielle Bonheur 'Coco' Chanel, Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Thierry Herms and Louis Vuitton have founded some of the most famous and popular fashion brands.

In the 16th century, fashion clothing in France dealt with contrast fabrics, clashes, trims and other accessories. Silhouette, which refers to the line of a dress or the garment's overall shape, was wide and conical for women and square for men in the 1530s. Around the middle of that decade, a tall and narrow line with a V-shaped waist appeared. Focusing on the shoulder point, sleeves and skirts for women were widened. Ruffles got associated with neckband of a shirt and was shaped with clear folds. A ruffle, frill, or furbelow is a strip of fabric, lace or ribbon tightly gathered or pleated on one edge and applied to a garment, bedding, or other textile as a form of trimming.

Outer clothing for women was characterised by a loose or fitted gown over a petticoat. In the 1560s, trumpet sleeves were rejected and the silhouette became narrow and widened with concentration in shoulder and hip.

Between 1660 and 1700, the older silhouette was replaced by a long, lean line with a low waist for both men and women. A low-body, tightly-laced dress was plaited behind, with the petticoat looped upon a pannier (part of a skirt looped up round the hips) covered with a shirt. The dress was accompanied by black leather shoes. Winter dress for women was trimmed with fur. Overskirt was drawn back in later half of the decades, and pinned up with the heavily-decorated petticoat. But around 1650, full, loose sleeves became longer and tighter. The dress tightly hugged the body with a low and broad neckline and adjusted shoulder.

Men's clothing did not change much in the first half of the 17th century. In 1725, the skirts of the coat acted as a pannier. This was brought about by making five or six folds distended by paper or horsehair and by the black ribbon worn around the neck to give the effect of the frill. A hat carried under the arm and a wig added to the charm. At court ceremonies, women wore a large coat embroidered with gold that was open in the front and buttoned up with a belt or a waist band. The light coat was figure-hugging with tighter sleeves. It was projected in the back with a double row of silk or metal buttons in various shapes and sizes.

French fashion varied between 1750 and 1775. Elaborate court dresses with enchanting colours and decoration defined style. In the 1750s, the size of hoop skirts got smaller and was worn with formal dresses with side-hoops. Use of waistcoats and breeches continued. A low-neck gown was worn over a petticoat during this period. Sleeves were cut with frills or ruffles with fine linen attached to the smock sleeves. The neckline was fitted with trimmed fabric or lace ruffle and a neckerchief (scarf).

Fashion between 1795 and 1820 in European countries transformed into informal styles involving brocades and lace. It was distinctly different from earlier styles as well as from the ones seen in the latter half of the 19th century. Women's clothes were tight against the torso from the waist upwards and heavily full-skirted. The short-waist dresses adorned with soft, loose skirts were fabricated with white, transparent muslin. Evening gowns were trimmed and decorated with lace, ribbons and netting. Those were cut low with short sleeves.

In the 1800s, women's dressing was characterised by short hair with white hats, trim, feathers, lace, shawls and hooded-overcoats while men preferred linen shirts with high collars, tall hats and short and wigless hair.

In the 1810s, dress for women was designed with soft, subtle, sheer classical drapes with raised back waist and short-fitted single-breasted jackets. Their hair was parted in the centre and they wore tight ringlets in the ears. Men's dress was fabricated with single-breasted tailcoats, cravats (the forerunner of the necktie and bow tie) wrapped up to the chin with natural hair, tight breeches and silk stockings. Accessories included gold watches, canes and hats.

In the 1820s, women's dress came with waist lines that almost dropped with elaborate hem and neckline decoration, cone-shaped skirts and sleeves. Men's overcoats were designed with fur of velvet collars.

Fashion designers still get inspired by 18th century creations. The impact of the 'clothing revolution' changed the dynamics of history of clothing. Paris is a global fashion hub and despite competition from Italy, the United Kingdom, Spain and Germany, French citizens continue to maintain their indisputable image of modish, fashion-loving people.

About the author

Abarrna Devi R is a final year B. Tech student in the department of fashion technology in Bannari Amman Institute of Technology, Sathyamangalam, Coimbatore, and Tamil Nadu.

References

1. Dauncey, Hugh, ed., French Popular Culture: An Introduction, New York: Oxford University Press (Arnold Publishers), 2003.

2. DeJean, Joan, the Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafes, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour, New York: Free Press, 2005, ISBN978-0-7432-6413-6

3. Kelly, Michael, French Culture and Society: The Essentials, New York: Oxford University Press (Arnold Publishers), 2001, (a reference guide)

4. Nadeau, Jean-Benot and Julie Barlow, Sixty Million Frenchmen Can't Be Wrong: Why We Love France but Not the French, Sourcebooks Trade, 2003, ISBN1-4022-0045-5

5. Bourhis, Katell le: The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789-1815, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989. ISBN0870995707

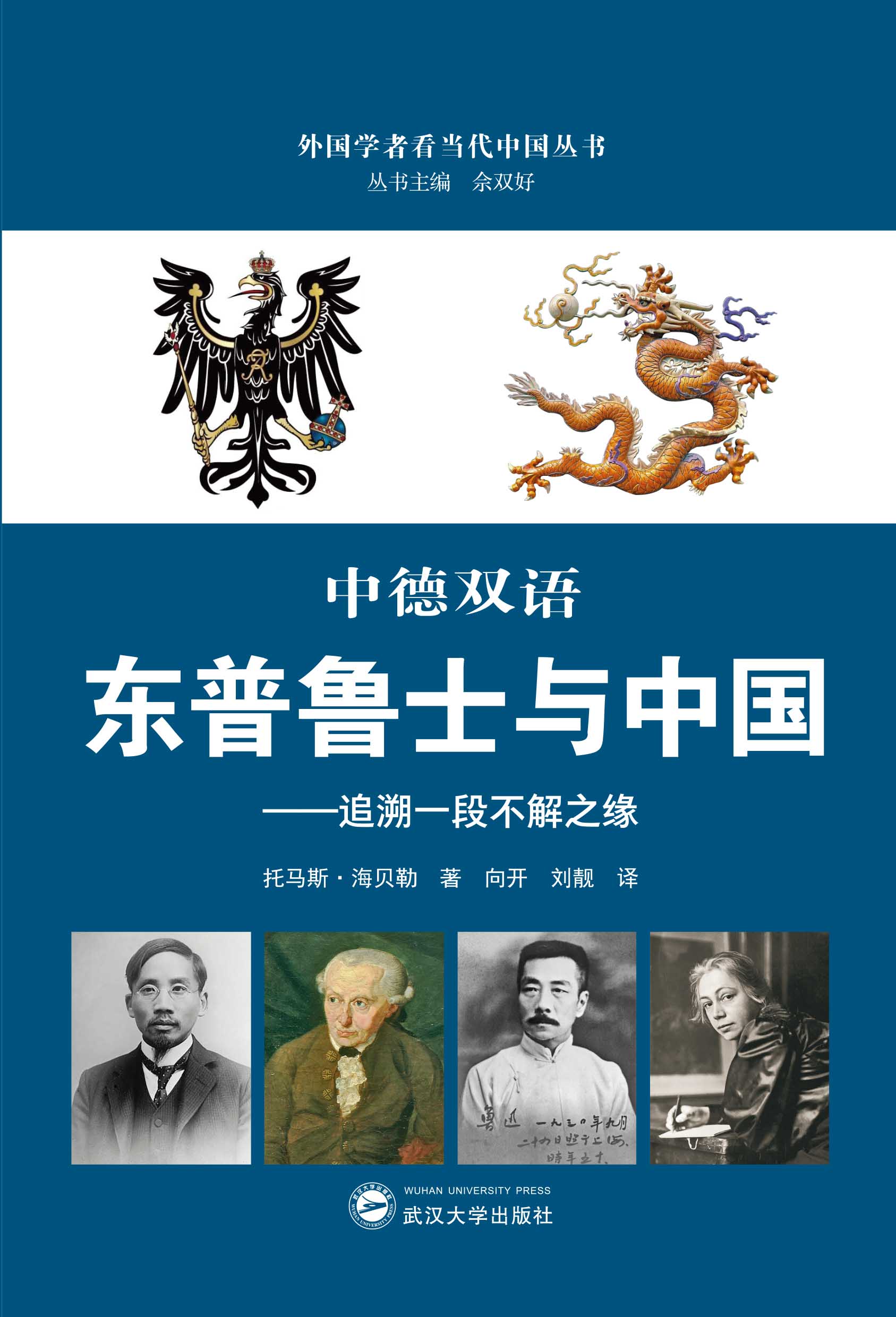

内容简介:

托马斯·海贝勒教授撰写的《东普鲁士与中国——追溯一段不解之缘》一书以东普鲁士与中国的深远关系为切入点,紧密结合了笔者的个人经历与职业背景,多层次、多角度地展示了一段至今仍未受到足够重视,未足够曝光的历史,寄望以这种方式丰富东普鲁士的记忆文化。 全书内容嵌在传记式的家族记忆框架里,读者可由此窥探笔者同中国、同东普鲁士之间的渊源,进而了解在探究这一主题过程中笔者的个人追求、兴趣和希冀。书中涉及大量具体的记忆形象和他(它)们与中国的联系,既包括与中国相关的人物,如中国研究学者、高级军官、外交官、传教士、建筑师,也包括出生在东普鲁士的思想家、科学家、艺术家、作家和诗人对中国产生的影响,还有那些研究解读他们思想精神的中国人,以及当地犹太人逃亡中国的历史等。海贝勒教授的追根溯源早已不囿于某个家族,而是立足中德双向视角,成功展现了一段延续至今,层次丰富的地区交往史。本书不涉及政治倾向性内容。

作者序:

如果作为研究中国的学者就东普鲁士与中国的关系撰文,绝不纯粹出于历史研究的学术兴趣,母亲家族与东普鲁士的渊源是我人生和身份的一部分,尽管我并不是在那里看到这个世界的第一缕光亮。母亲对东普鲁士的记忆深深烙印在我的脑海里,强化了我对自己这一层身份的认同,下文对此还将详述。

家族记忆是记忆文化的组成部分,在一个家族里它以这样的形式世代传承,影响着族人们的世界观和个人行为。(因萨尔茨堡新教流亡者身份而)遭人排挤的体验,祖父为了认识更广阔的世界冲出东普鲁士村庄那一方局促天地的决然之举,还有东普鲁士人对东部(与其接壤各国)依然保有的真挚坦率等等,都是这份家族记忆和认知储备的一部分,只是这样的东普鲁士仅留存在某些人的记忆里,他们要么曾经与此有所关联或者尚有关联,要么在那里出生,又或是探究到其家族与东普鲁士之间的渊源。

撰写此书是为了追忆这个曾经的德国东部省份以及当地人民为中德关系所作出的贡献,但同时这也是对德国乃至欧洲“集体记忆”的一次记念。对历史事件和人物,对文化、艺术、科学、哲学、政治及经济各领域演进过程的回忆,都是记忆文化和集体记忆的一部分。记忆文化则有利于群体与身份意识的创建。

全书以东普鲁士与中国的深远关系为切入点,将笔者的个人经历与职业背景紧密结合在一起。

全书共分九章,导言之后的第二至第四章主要涉及以下内容:首先是作为家族记忆文化一部分的家族东普鲁士背景(埃本罗德与施洛斯伯格)和家族在东普鲁士的生活史;其次是我对2017年前往埃本罗德和施洛斯伯格(东普鲁士)的寻根之旅的一些思考;然后将讲述我的中国之路、我的职业和在中国最初接触到的那些与东普鲁士或普鲁士有关的人与事。第五章探讨的是东普鲁士与中国之间的关系以及究竟是什么将它们联系了起来,这里将谈到普鲁士的亚洲政策、腓特烈大帝的中国情结、德国留在中国的“遗产”(亦或说德国镇压义和团运动及殖民青岛所犯下的“罪行”更为合适?)以及东普鲁士王宫之内所谓“中国热”的意义。这一章还将特别关注纳粹主义带来的灾难,它迫使大量原本生活在东普鲁士的犹太人在条件允许的情况下逃往上海,也导致中国传奇元帅朱德之女朱敏被拘禁于东普鲁士的一所集中营,这两个事件都是我前文所界定的“伦理记忆文化”的重要组成部分。第六章主要讲述东普鲁士作为德国汉学发源地的问题和东普鲁士在华传教士的活动。

对思想“先贤”康德和赫尔德及其与中国的渊源,以及他们对现代中国和中国形象的形成发展所产生的影响本书也将专章论述(第七章)。最后在第八章将谈及一系列具有代表性的东普鲁士名人,包括自然科学家、作家、政治理论家、艺术家以及商人,他们当中有历史人物,但也不乏出生在东普鲁士,却并没有在那里成长的当代名人。本章提到的历史名人有天文学家、数学家尼古拉·哥白尼,数学家、物理学家克里斯蒂安·哥德巴赫,大卫·希尔伯特,赫尔曼·闵可夫斯基和阿诺德·索末菲,女版画家、雕塑家凯绥·珂勒惠支,女政治理论家汉娜·阿伦特,女革命家王安娜,还有出生于东普鲁士的共产国际代表亚瑟·埃韦特和亚瑟·伊尔纳(别名理查德·施塔尔曼)及其在中国的活动,以色列女政治家、作家利亚·拉宾,外交家阿瑟·齐默尔曼也在此列;当代名人则包括建筑师福尔克温·玛格,雕塑家、装置艺术家胡拜图斯·凡·登·高兹,电子音乐的先锋人物、“橘梦乐团”创始人埃德加·福乐斯以及美国传奇蓝调摇滚乐队“荒原狼”主唱约阿希姆·弗里茨·克劳雷达特(约翰·凯)等。出现在本书中的还有海因里希·冯·克莱斯特和托马斯·曼的东普鲁士岁月,著名的尼达艺术家之村,以及多位在中国曾经或依然被关注研究(接受)的东普鲁士名人,他们当中有同中国有生意往来的商贾,也有二战中既在东普鲁士又在中国抗日战场参战的苏联元帅。部分苏联军队在东普鲁士的表现一定程度上与其1945年在中国东北的所作所为相似,这一切分别存留在德国和中国民众的集体记忆里,或许正是这些使许多中国人在面对东普鲁士平民的悲剧时多少有些感同身受。

本书并不着力探究普鲁士与中国交往的历史,对此学者们已有著述,这里更多关注的是与那个曾经属于德国,如今分属俄罗斯、波兰和立陶宛的省份,以及与此相关的记忆形象和他(它)们与中国的缘分,既包括与中国有联系的人物、中国问题学者、高级军官、外交官、传教士、建筑师,也包括出生在东普鲁士的思想家、科学家、艺术家、作家和诗人对中国产生的影响,还有那些研究解读他们思想精神的中国人,以及当地犹太人逃亡中国的历史等。本书无意全面探究所有这些联系,对笔者而言关键是对这些记忆形象的收录整理,不拘泥于细节,本来写作初衷就是以勾勒轮廓框架为先,勘明趋势与特征,并非还原事件经过。全书内容嵌在传记式的家族记忆框架里,读者可由此窥探笔者同中国、同东普鲁士之间的渊源,进而了解在探究这一主题过程中笔者的个人追求、兴趣和希冀,这些传记性内容见于本书第二章,第三章则是在此框架下对“故乡”概念的简短反思——探讨究竟何为“故乡”。总之,撰写这本书是一次尝试,尝试记录东普鲁士乃至德国的一段历史,一段至今仍未受到足够重视,未足够曝光的历史,寄望以这种方式去丰富东普鲁士的记忆文化。

东普鲁士在其历史上既是一个多民族地区,也是一个移民地区。条顿骑士团(亦称德意志骑士团)东征前,西波罗的海沿岸地区生活着古普鲁士人。在骑士团间或野蛮的殖民过程中,来自德意志帝国的拓荒者不断涌入,此外还有斯堪的纳维亚人、瑞士人、波兰人、俄罗斯人、捷克人、法国人和受洗的立陶宛人,他们与当地原住民聚居融合,14世纪又有不少马祖里人、立陶宛人和鲁提尼人迁居于此。随着15世纪条顿骑士团历经一系列损失惨重的战役走向没落,来自波兰、俄国和立陶宛的移民在此安家落户。伴随着宗教改革运动,欧洲第一个新教国家普鲁士公国建立,更广泛的宗教自由吸引了整个欧洲的新教和加尔文教派信徒,他们不仅来自德意志帝国,还从波兰、立陶宛、荷兰、法国(胡格诺教派信徒)、苏格兰、俄国、奥匈帝国迁徙而来,甚至还有主要由俄国而来的犹太人。

17世纪塔塔尔族人的袭扰和1709年至1711年间泛滥的鼠疫造成东普鲁士全境人口锐减,于是普鲁士国王着力推动瑞士加尔文派信徒以及萨尔兹堡的新教流亡者来本国定居,这两大群体中的大部分人都是熟练工匠。此举造成东普鲁士居民来源复杂多样,使建立德语教育机构和使用德语授课成为促进这些移民群体统一与融合的手段,这个目标遂成为腓特烈·威廉一世1713年引入普通义务教育的原因之一。

无论是当地非德意志的原生民族,还是来自四面八方的移民,都为东普鲁士增添了新的元素,对它产生了影响,进而在这片土地上留下各自的印迹,为其发展和多元化贡献了自己的力量。此外,在东普鲁士的历史上,该地区始终与波兰、俄国和波罗的海诸国保持着紧密的关系和深入的交流。对此阿明·缪勒-斯塔尔是这样说的:交织在一起的关系网“层层叠叠,密密实实”,在造就多元文化精英方面功不可没。

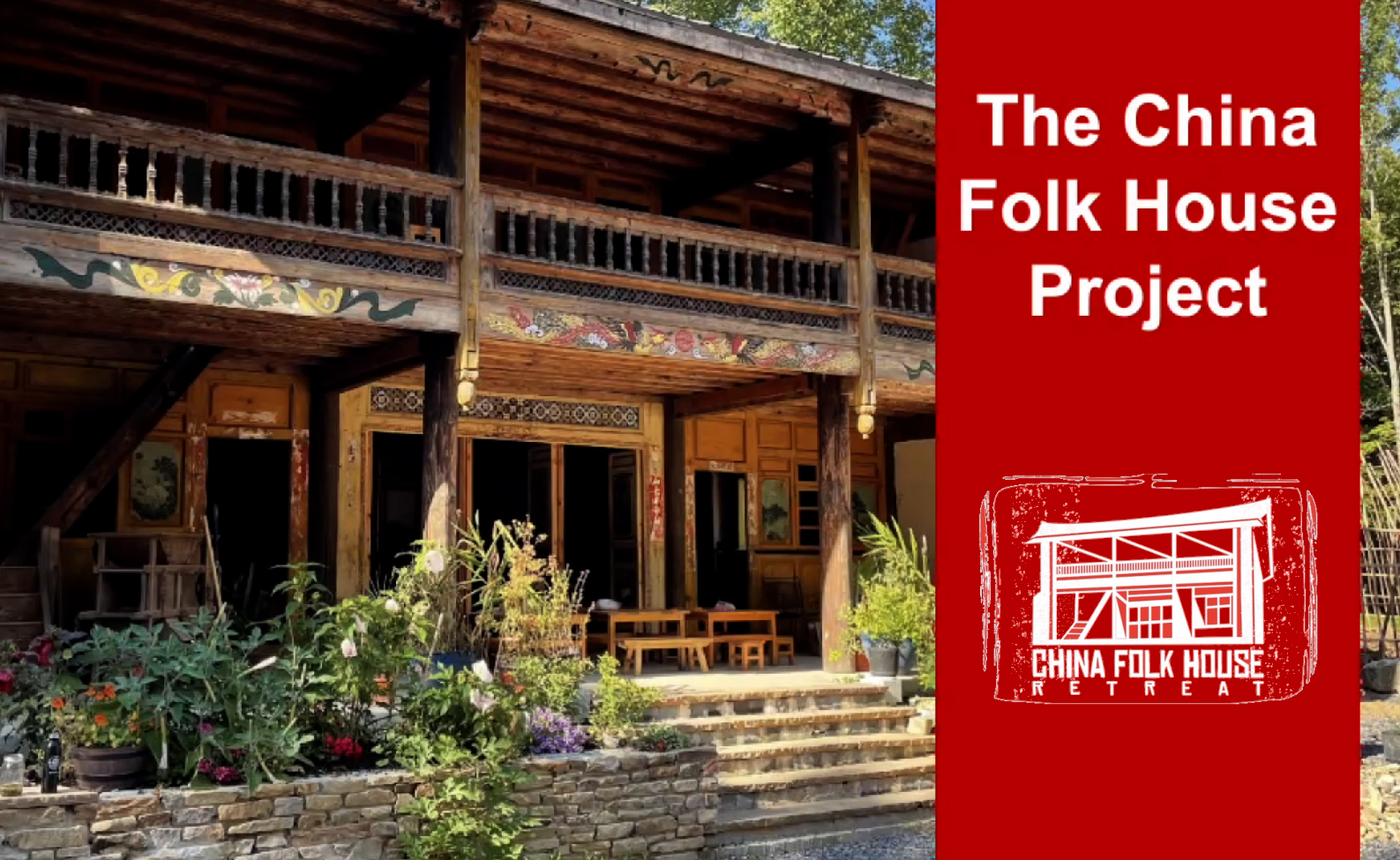

The China Folk House Retreat is a Chinese folk house in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, United States, reconstructed from its original location in Yunnan in China. A non-profit organization dismantled and rebuilt it piece by piece with the goal to improve U.S. understanding of Chinese culture.

History

John Flower, director of Sidwell Friends School's Chinese studies program, and his wife Pamela Leonard started bringing students to Yunnan in 2012 as part of a China fieldwork program. In 2014 Flower, Leonard, and their students found the house in a small village named Cizhong (Chinese: 茨 中) in Jianchuan County of Yunnan, China. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, they brought dozens of 11th and 12th-grade students to Yunnan to experience the cultural and natural environment of this province every spring. The architectural style of this house is a blend of Han, Bai, Naxi and Tibetan styles.

The Cizhong Village is located in eastern Himalaya, alongside the Mekong River. It has a long history of Sino-foreign cultural exchanges. The Paris Foreign Missions Society established the Cizhong Catholic Church in 1867. When they visited the village, Zhang Jianhua, owner of the house, invited them to his home. Zhang told them that the house was built in 1989, and would be flooded by a new hydroelectric power station. While the government built a new house for him one kilometer away, Flower came up with the idea of dismantling the house and rebuilding it in the United States. This house was built using mortise and tenon structure, which made it easy to be dismantled.

Logistics

Flower and his students visited Zhang several times and eventually bought the house from him. After measurements and photographing, the whole house was dismantled, sent to Tianjin and shipped to Baltimore, and finally to West Virginia. Since 2017, they have spent several years rebuilding the house in Harpers Ferry, at the Friends Wilderness Center, following the traditional Chinese method of building. For the development of this project, Flower and Leonard formed the China Folk House Retreat.

Amphitrite, femme de Poséidon dans la mythologie grecque, est également le nom du premier vaisseau français à accoster sur les côtes chinoises. Après les Portugais, les Hollandais et les Anglais, la France entreprend, grâce à ce navire, le commerce direct avec La Chine. Au tournant du XVIIIe siècle, le vaisseau réalise ainsi deux expéditions.

Genèse du premier voyage de l’Amphitrite

L’histoire de ce vaisseau débute bien avant son départ pour Canton le 6 mars 1698 car le projet de cette expédition naît à Pékin et non en France. Lors de l’ambassade française au Siam en 1685, le vaisseau l’Oiseau embarque à son bord six jésuites qui doivent rallier la capitale impériale. Parmi eux figurent le père Joachim Bouvet (1656-1730) et le père Jean de Fontaney (1643-1710) . Après quelques années, l’empereur chinois Kangxi (1654-1722), avide de savoirs occidentaux, mandate le père Joachim Bouvet afin de ramener en Chine de nouveaux missionnaires français. Désigné « envoyé spécial de l’Empereur », le père Joachim Bouvet rentre en France en mars 1697.

Histoire de l’armement

En avril 1687, le père est reçu par Louis XIV qui n’est pas très enthousiaste dans un premier temps par ce voyage mais il se laisse convaincre car l’expédition représenterait une aide conséquente à la conversion de l’empire chinois. Néanmoins, le père jésuite ne parvient pas à obtenir le titre de vaisseau du roi. Après avoir contacté la Compagnie des Indes françaises qui se montre réticente à cette entreprise qu’elle juge audacieuse et risquée, le père Bouvet se tourne vers Jourdan de Groussey, responsable des ventes de la manufacture des glaces. Via le comte de Pontchartrin, le vaisseau l’Amphitrite de 500 tonneaux est acheté puis rapidement chargé de quantité de glaces, de marqueterie française, de portraits de la cour, de pendules, de montres et de liqueurs. Le récit de voyage de Froger, matelot sur le vaisseau, est très instructif sur la cargaison et sur leur finalité. Il fournit également de nombreux détails sur la route empruntée et la direction des vents. Celui du peintre italien Gio Ghirardini est plus pittoresque que le récit de Froger de la Rigaudière car il relate son expérience personnelle. En raison du manque de sources manuscrites sur le premier envoi, lacune qui est remarquée par Paul Pelliot, les récits de voyage constituent les premiers documents mobilisables pour connaître les détails de l’expédition.

De son départ de la Rochelle le 6 mars 1698 jusqu’à Canton le 2 novembre 1698, le voyage se déroule sans embûche même si l’équipage manque le détroit de la Sonde. Une fois arrivé à Canton, le statut du navire pose problème. Si Louis XIV n’a pas autorisé le titre de vaisseau du roi à l’Amphitrite, afin de ne pas froisser les Portugais, le père Joachim Bouvet affirme pourtant bien le contraire au capitaine de La Roque. Néanmoins, l’ambivalence de statut du navire, vaisseau marchand ou vaisseau de tribut, entraîne nombre de complications au sujet de la cargaison et des taxes à acquitter. Le vaisseau est finalement exempté de toutes les taxes marchandes et les biens destinés à la cour sont bien acheminés jusqu’à Pékin. Déchargement puis chargement ont entraîné de nombreux retard et l’Amphitrite ne repart de Canton que quatorze mois plus tard, le 26 janvier 1700.

Retour et second voyage

Le retour du vaisseau à Lorient le 3 août 1700 et la vente des produits chinois à Nantes est à la hauteur des ambitions placées dans l’expédition. La soie est autorisée à être écoulée en France tandis que les porcelaines des 181 caisses de la cargaison de retour se vendent très bien et font sensation en France. A partir de ce premier voyage, l’Amphitrite est armé une deuxième fois le 7 mars 1701 pour la même destination. Si le premier voyage ne fut qu’une tentative en vue d’établir des connaissances plus précises sur les biens commercialisables en Chine, les informations rapportées ont été très instructives pour le second envoi et rendent les deux expéditions indissociables l’une de l’autre. Elles ont également de grandes similitudes telles que l’établissement du commerce français dans cette région, la mise en place de deux ambassades officieuses, et le rôle des jésuites comme intermédiaires culturels. Sur ce point, le père Jean de Fontaney est au second voyage de l’Amphitrite ce que le père Bouvet fut pour le premier. Il rentre en France au terme du premier voyage du vaisseau et contribue à la mise en place de la seconde expédition. Savary des Bruslons, dans Le Dictionnaire universel du commerce, détaille par ailleurs la cargaison aller pour ce deuxième voyage. Cependant, le second voyage connaît de plus grandes difficultés (exemption refusée, démâtage, perte de l’ancre et de nombreux morts). Il laisse plus de 100 000 livres de pertes et représente ainsi une grande déception sur le plan commercial.

Considéré par Paul Pelliot comme le point de départ des relations franco-chinoises, l’Amphitrite ouvre la voie a plusieurs dizaines de vaisseaux français tout le long du XVIIIe siècle.

Légende de l'image : Le voyage en Chine : esquisse de décor de l'acte III : le bateau à vapeur " la pintade". P. Chaperon

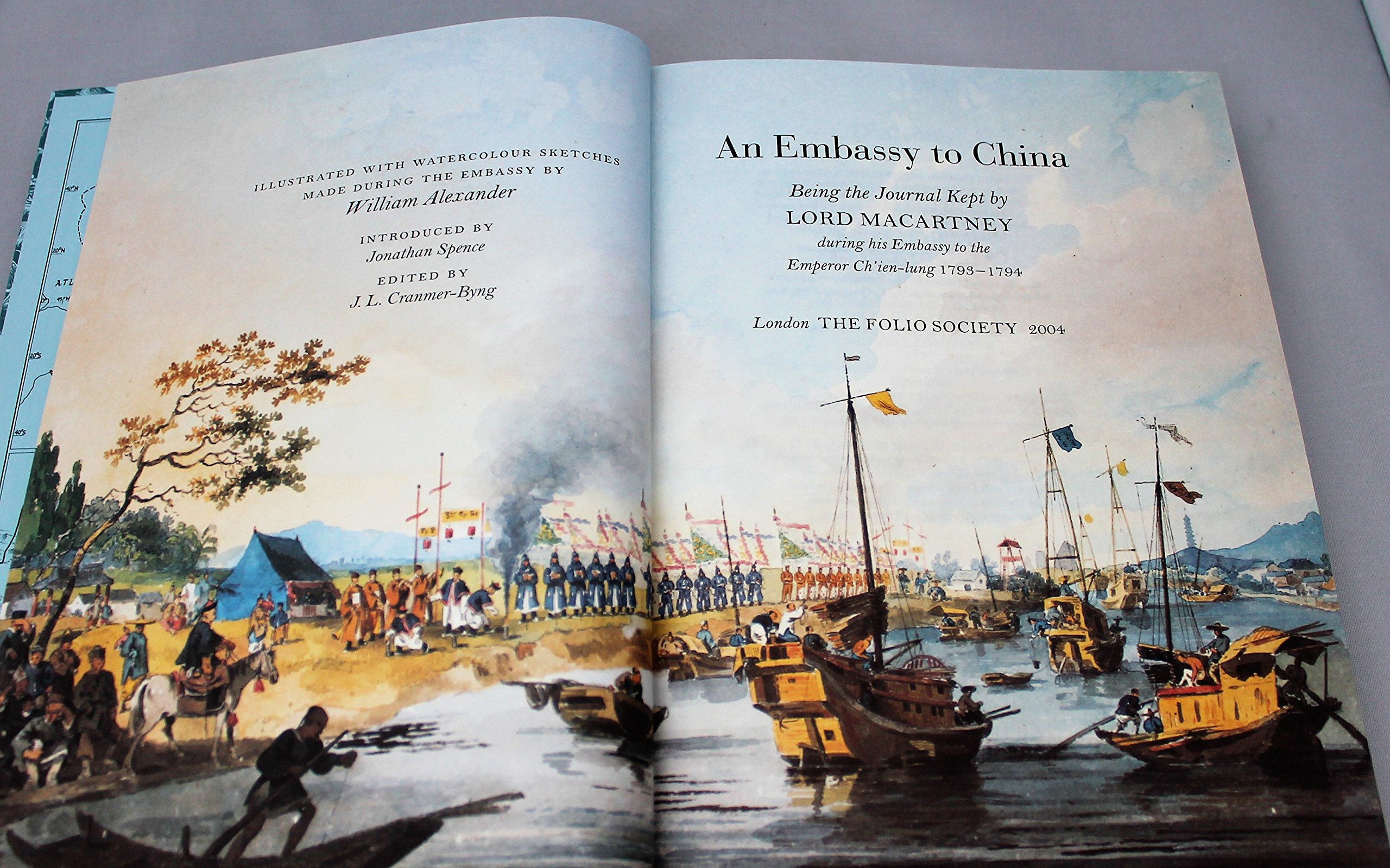

The Macartney Embassy (Chinese: 馬加爾尼使團), also called the Macartney Mission, was the first British diplomatic mission to China, which took place in 1793. It is named for its leader, George Macartney, Great Britain's first envoy to China. The goals of the mission included the opening of new ports for British trade in China, the establishment of a permanent embassy in Beijing, the cession of a small island for British use along China's coast, and the relaxation of trade restrictions on British merchants in Guangzhou (Canton). Macartney's delegation met with the Qianlong Emperor, who rejected all of the British requests. Although the mission failed to achieve its official objectives, it was later noted for the extensive cultural, political, and geographical observations its participants recorded in China and brought back to Europe.

Foreign maritime trade in China was regulated through the Canton System, which emerged gradually through a series of imperial edicts in the 17th and 18th centuries. This system channeled formal trade through the Cohong, a guild of thirteen trading companies (known in Cantonese as "hong") selected by the imperial government. In 1725, the Yongzheng Emperor gave the Cohong legal responsibility over commerce in Guangzhou. By the 18th century, Guangzhou, known as Canton to British merchants at the time, had become the most active port in the China trade, thanks partly to its convenient access to the Pearl River Delta. In 1757, the Qianlong Emperor confined all foreign maritime trade to Guangzhou. Qianlong, who ruled the Qing dynasty at its zenith, was wary of the transformations of Chinese society that might result from unrestricted foreign access.[1] Chinese subjects were not permitted to teach the Chinese language to foreigners, and European traders were forbidden to bring women into China.[2]: 50–53

By the late 18th century, British traders felt confined by the Canton System and, in an attempt to gain greater trade rights, they lobbied for an embassy to go before the emperor and request changes to the current arrangements. The need for an embassy was partly due to the growing trade imbalance between China and Great Britain, driven largely by the British demand for tea, as well as other Chinese products like porcelain and silk. The East India Company, whose trade monopoly in the East encompassed the tea trade, was obliged by the Qing government to pay for Chinese tea with silver. To address the trade deficit, efforts were made to find British products that could be sold to the Chinese.

At the time of Macartney's mission to China, the East India Company was beginning to grow opium in India to sell in China. The company made a concerted effort starting in the 1780s to finance the tea trade with opium.[3] Macartney, who had served in India as Governor of Madras (present-day Chennai), was ambivalent about selling the drug to the Chinese, preferring to substitute "rice or any better production in its place".[2]: 8–9 An official embassy would provide an opportunity to introduce new British products to the Chinese market, which the East India Company had been criticised for failing to do.[4]

In 1787, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and East India Company official Henry Dundas dispatched Colonel Charles Cathcart to serve as Britain's first ambassador to China. Cathcart became ill during the voyage, however, and died just before his ship, HMS Vestal, reached China. After the failure of the Cathcart Embassy, Macartney proposed that another attempt be made under his friend Sir George Staunton. Dundas, who had become Home Secretary, suggested in 1791 that Macartney himself take up the mission instead. Macartney accepted on the condition that he would be made an earl, and given the authority to choose his companions.

Macartney chose George Staunton as his right-hand man, whom he entrusted to continue the mission should Macartney himself prove unable to do so. Staunton brought along his son, Thomas, who served the mission as a page. John Barrow (later Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet) served as the embassy's comptroller. Joining the mission were two doctors (Hugh Gillan[5][6] and William Scott), two secretaries, three attachés, and a military escort. Artists William Alexander and Thomas Hickey would produce drawings and paintings of the mission's events. A group of scientists also accompanied the embassy, led by James Dinwiddie.[2]: 6–8

It was difficult for Macartney to find anyone in Britain who could speak Chinese because it was illegal for Chinese people to teach foreigners. Chinese who taught foreigners their language risked death, as was the case with the teacher of James Flint, a merchant who broke protocol by complaining directly to Qianlong about corrupt officials in Canton.[7] Macartney did not want to rely on native interpreters, as was the custom in Canton.[8] The mission brought along four Chinese Catholic priests as interpreters. Two were from the Collegium Sinicum in Naples, where George Staunton had recruited them: Paolo Cho (周保羅) and Jacobus Li (李雅各; 李自標; Li Zibiao).[9] They were familiar with Latin, but not English. The other two were priests at the Roman Catholic College of the Propaganda, which trained Chinese boys brought home by missionaries in Christianity. The two wanted to return home to China, to whom Staunton offered free passage to Macau.[2]: 5 [10] The 100-member delegation also included scholars and valets.[11]

Among those who had called for a mission to China was Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, President of the Royal Society. Banks had been the botanist on board HMS Endeavour for the first voyage of Captain James Cook, as well as the driving force behind the 1787 expedition of HMS Bounty to Tahiti. Banks, who had been growing tea plants privately since 1780, had ambitions to gather valuable plants from all over the world to be studied at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew and the newly established Calcutta Botanical Garden in Bengal. Above all, he wanted to grow tea in Bengal or Assam, and address the "immense debt of silver" caused by the tea trade. At this time, botanists were not yet aware that a variety of the tea plant (camellia sinensis var. assamica) was already growing natively in Assam, a fact that Robert Bruce was to discover in 1823. Banks advised the embassy to gather as many plants as possible in their travels, especially tea plants. He also insisted that gardeners and artists be present on the expedition to make observations and illustrations of local flora. Accordingly, David Stronach and John Haxton served as the embassy's botanical gardeners.[12]

1776年7月4日是美国建国,然后经历从1775年至1783年长达8年的独立战争,迫使英国承认美国独立。为走出战争后经济危机和英国贸易禁运的带来的困境境,美国银行家、商人罗伯特·莫里斯建议政府派船到中国寻求新的商机,帮助美国渡过难关。这是一个发展中的国家,对一个发达国家的期盼。

“中国皇后号”,向大清致敬的美国船

说干就干,莫里斯联合纽约商界著名人士,投资12万美元,共同购置了一艘360吨的术制军舰,配有各种新式航海设备。为讨好中国,他们将这艘改装商船起名为“中国皇后号”(The Empress Of China)。莫里斯将从海军中挑选出来的格林聘为船长,并邀请山茂召作为他的商务代理人。

独立战争胜利的第二年,1784年1月30日,美国政府给该船颁发加盖了美利坚合众国大印的航海证书,因为无法估计到中国当时的国体政情,美国人在证书上空前绝后地写上了无数头衔:君主、皇帝、国王、亲王、公爵、伯爵、男爵、勋爵、市长、议员……为隆重起见,甚至连起航日期也精挑细选,最后选定了一个当时公认的“黄道吉日”:1784年2月22日——首任总统华盛顿的生日。一条中等级美国商船就这么冒险驶上了通往东方的航路。

今天的中国人了解“中国皇后号”多是通过美国人的一部专著。1984年美国费城海事博物馆,在纪念“中国皇后号”首航广州200周年的时候,出版了菲利普·查德威克·福斯特·史密斯《中国皇后号》一书。此书引起了早就忘了“中国皇后号”这件事的中国人的兴趣,2007年广州出版社出版了《中国皇后号》的中文版,公众这才知道,“海上丝绸之路”还有一段中美贸易传奇。

停泊在纽约的“中国皇后号”

那么,大清国与美国当时相互都有什么贸易需求呢?

据记载,当年“中国皇后号”载着473担两洋参、2600张毛皮、1270匹羽纱、26担胡椒、476担铅、300多担棉花及其他商品——驶向中国。后来,澳门出版《中国丛报》特别介绍过西洋参在中国销售的重要性:“产于鞑靼和美洲,从美洲又出产到中国,大多数医生把它看成灵丹妙药,也成为鞑靼皇帝的财物,每年赐给下面宠信的臣子……”,此后,美国商船,每来中国必定带西洋参到中国销售。

1784年8月,“中国皇后号”终于到了当时作为中国海上门户之一的澳门,在这里取得了一张盖有清廷官印的“中国通行证”,获准进入珠江,在大清领航员的带领下,“中国皇后号”经过一天的航行,抵达广州的黄埔港。“中国皇后号”呜礼炮十三响(代表当时美国的十三个州)。格林船长曾有一则这样的手记:“‘中国皇后号’荣幸地升起了在这海域从未有人升起或看见过的第一面美国国旗,这一天是1784年8月28日。”当时的两洋画家创作了一幅《“中国皇后号”到达广州》,记录下了这一中国美海上贸易的重要场景。

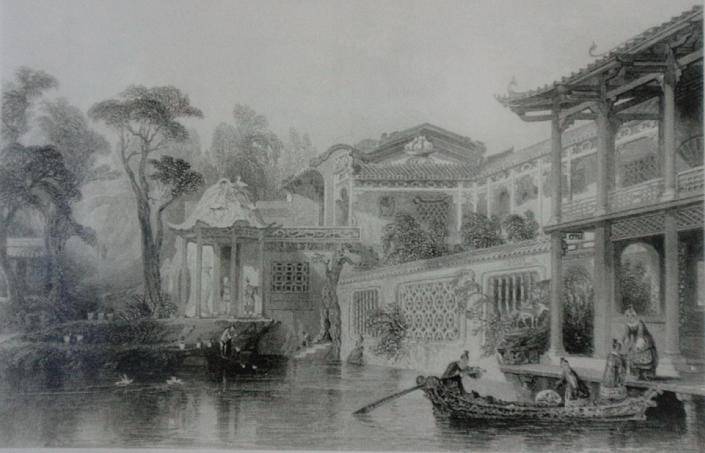

欧洲铜版画中的广州十三行风景

4个月后,“中国皇后号”的货物已全部脱手,并采办了一大批中国货:红茶2460担、绿茶562担、瓷器962担,还有大量丝织品、象牙扇、梳妆盒、手工艺品等等,船长格林本人,还购买了男士缎裤300余条、女士长袖无指手套600副、象牙扇100把。美国商人心满意足地踏上归程。

1785 年 5 月 11 日,“中国皇后号”回到纽约,往返历时 15 个月。“中 国 皇后号 ”回到纽约后,立刻刊登出售 中 国商品的广告。结果, 12 万美元购得的中国货,立即销售一空。华盛顿本人也购买了 302 件瓷器及绘有图案的茶壶、精美象牙扇等中国货。这些物品仍有部分保留在美国宾州博物馆和华盛顿故居内(第二次“中国皇后号”的中国之行,华盛顿夫人特别点名要买一批中国白瓷) 。

这次航行的美同商人获利只有3万多美元,但它开启了新的贸易窗口,挣脱了英国的经济封锁,这对当时的美国实在是太重要了。所以,相关人等被纷纷提拔,莫里斯一跃成为美国联邦政府第一任财政部长;船长格林则成为后来与中国通商的著名顾问,而商务代理人山茂召更是声名鹊起。山茂召回到美国后,立刻向当时联邦政府的外交国务秘书约翰·杰伊递交了“‘中国皇后号’访华报告”,报告赞许了中国人的好客和宽厚,极力倡导对华贸易。国会经讨论后,面向全国发布了对此次航行的表扬信,一时间,引发了全美的“中国热”。

“广州”:美国小城最喜欢起的名字

清初,以广州为目的地的海上贸易航线已有多条,“中国皇后号”的到来,又增加了一条美国直达广州的航线。作为当时中国主要对外贸易的唯一港口的广州,则成为吸引美国的最著名城市。

29岁商务代理人山茂召在他的首航中国日记中说:“虽然这是第一艘到中国的美国船,但中国人对我们却非常的宽厚。最初,他们并不能分清我们和英国人的区别,把我们称为‘新公民’,但我们拿美国地图向他们展示时,在说明我们的人口增长和疆域扩张的情况时,商人们对我围拥有如此之大的,可供他们帝国销售的市场,感到十分的高兴。”

1786年1月,山茂召因对中美贸易的贡献被美国任命为驻广州领事,山茂召一任5年,此间,不仅有几百吨的大商船前往中国,连一些几十吨的小船也载着有限的货物驶向广州,在通往中同的航线上,美国商船绵延不断,成为一大奇观。美国商船多次来广州的成功贸易,吸引了更多的美国商人投资这一贸易,波士顿商人竞发行每股300美元的大额对华贸易股票。

1793年2月,山茂召踏上了第4次中国之旅。11月2日,山茂召一行从孟买顺利到达了广州,但是次年3月他乘坐“华盛顿号”返航时,肝病恶化,客死返航途中,时年39岁,从而结束了他10年问往返中美的辉煌贸易生涯。而此时,中美海上贸易已经迅速超过荷兰、丹麦、法国,仅次于英国,排在世界的第二位。

由于当时中国对外贸易窗口,只剩下广州一地通商,所以,广州成了成功与繁荣的代名同,令没能来中国的美国人艳羡不已。因此,很多美国城镇就以“广州”(Canton)命名,而显其时尚。据说,美同的第一个“广州”,出现于1789年的乌萨诸塞州东部诸福克县的广州镇。后来,义有了俄亥俄州东北部的“广州”,它是美国最大的“广州”。美国学者乔治·斯蒂华特在一本研究美国地名的著作中曾提到:当时,在美国23个州里,都有以广州命名的城镇或乡村。与“广州”大热相反的是,大清最有学问“一代硕学”阮元在当两广总督时,于清嘉庆二十二年(1817年)编著《广州通志》,竟然还把美国说成是“在非洲境内”。

美国山寨中国的地名

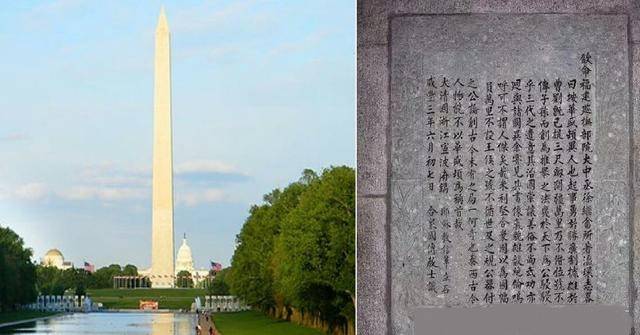

藏在方尖碑里的里程碑

现在到美国旅游的人,都少不了到华盛顿转一转。但很少有人注意到华盛顿纪念碑即著名的方尖碑里还有一段中国故事。此碑高169.045米,碑内有50层铁梯,也设有70秒到顶端的高速电梯,在纪念碑内墙镶嵌着188块由私人、团体及全球各地捐赠的纪念石,其中就镶嵌有一块中文石碑,碑高1.6米,宽1.2米,它是“中国皇后号”首航中国70年后,于清咸丰三年(1853年)由中国漂洋过海,赠予美国,作为送给华盛顿纪念碑的特殊礼品。

华盛顿纪念碑和纪念碑上镶嵌的中文碑

需要指出的是,此碑并非大清政府所送,碑文落款:“大清国浙江宁波府镌,耶稣教信辈立石,合众国传教士识。”这位刻石的宁波知府,名叫毕永绍,上任不到一年,就离职了。碑文正文是由美国传教士丁韪良推荐,它来自曾任福建巡抚的徐继畲所著《瀛环志略》。此书初刻于道光二十八( 1848年),后来被清廷查禁了。徐继畲是中国最早的“美国通”,他第一次把华盛顿介绍到了中国:“华盛顿,异人也。起事勇于胜、广,割据雄于曹、刘。既已提三尺剑,开疆万里,乃不僭位号,不传子孙,而创为推举之法,几于天下为公,骎骎乎三代之遗意。其治国崇让善俗,不尚武功,亦迥与诸国异”、“呜呼,可不谓人杰矣哉!米利坚合众国以为围,幅员万里,不设王侯之号,不循世及之规,公器付之公论,创古今未有之局,一何奇也!泰丙古今人物,能不以华盛顿为称首哉!”这两段赞美华盛顿话,通过立石刻碑,送到美国,也让美国人第一次知道了中国还有人如此赞美美国领袖。

如果我们细想一下,徐继畲的《瀛环志略》,仅比魏源六十卷本《海国图志》晚了1年。但在“制夷”与“开眼向洋”的方向上,则大有不同,而比之托克维尔的1840年完成《论美国的民主》仅晚了8年。

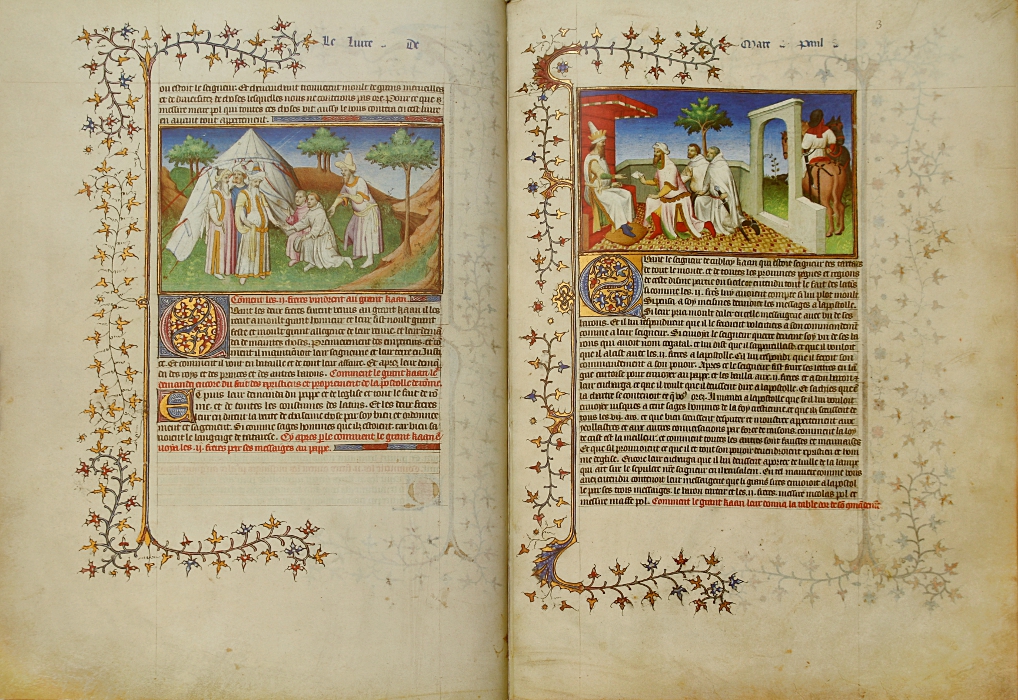

Le Livre des merveilles et autres récits de voyages et de textes sur l’Orient est un manuscrit enluminé réalisé en France vers 1410-1412. Il s'agit d'un recueil de plusieurs textes évoquant l'Orient réunis et peints à l'attention de Jean sans Peur, duc de Bourgogne, contenant le Devisement du monde de Marco Polo ainsi que des textes d'Odoric de Pordenone, Jean de Mandeville, Ricoldo da Monte Croce et d'autres textes traduits par Jean le Long. Le manuscrit contient 265 miniatures réalisées par plusieurs ateliers parisiens. Il est actuellement conservé à la Bibliothèque nationale de France sous la cote Fr.2810.

Le manuscrit, peint vers 1410-1412, est destiné au duc de Bourgogne Jean sans Peur, dont les armes apparaissent à plusieurs reprises (écartelé aux 1 et 4 de France à la bordure componée d’argent et de gueules, aux 2 et 3 bandé d’or et d’azur à la bordure de gueules), ainsi que ses emblèmes (la feuille de houblon, le niveau, le rabot). Son portrait est représenté au folio 226, repeint sur un portrait du pape Clément V. Le manuscrit est donné en janvier 1413 par le duc à son oncle Jean Ier de Berry, comme l'indique l'ex-libris calligraphié en page de garde. L'écu de ce dernier est alors repeint à plusieurs endroits sur celui de son neveu. Le livre est signalé dans deux inventaires du prince en 1413 et 1416. À sa mort, le livre est estimé à 125 livres tournois1.

Le manuscrit est ensuite légué à sa fille Bonne de Berry et à son gendre Bernard VII d'Armagnac. Il reste dans la famille d'Armagnac jusqu'aux années 1470. Il appartient à Jacques d'Armagnac lorsqu'une miniature est ajoutée au folio 42v. et son nom ajouté à l'ex-libris de la page de garde. Arrêté et exécuté en 1477, sa bibliothèque est dispersée et l'emplacement du manuscrit est alors inconnu. Un inventaire de la bibliothèque de Charles d'Angoulême mentionne un Livre des merveilles du monde qui pourrait être celui-ci. Il se retrouve ensuite peut-être dans la bibliothèque privée de son fils, le roi François Ier. Avec le reste de ses livres, il entre dans la seconde moitié du xvie siècle dans la bibliothèque royale et il est mentionné dans l'inventaire de Jean Gosselin.

《Chinese characteristics》(中国人的性格)是西方人介绍研究中国民族性格的最有影响的著作。由美国公理会来华传教士明恩溥(Arthur Henderson Smith)撰写。书中描述了100多年前中国人,有高尚的品格、良好的习惯。也有天生的偏狭、固有的缺点。此为1894年刊本。

明恩溥的《中国人的性格》一书的内容1890年曾在上海的英文版报纸《华北每日新闻》发表,轰动一时;1894年在纽约由弗莱明出版公司结集出版。这位博学、不无善意的传教士力图以公允的态度叙述中国。他有在中国生活22年的经验为他的叙述与评价担保,他看到中国人性格的多个侧面及其本相的暖昧性。他为中国人的性格归纳了20多种特征,有褒有贬,并常能在同一,问题上看到正反两方面的意义。《中国人的性格》在近半个世纪的时间里,不仅影响了西方人、日本人的中国观,甚至对中国现代国民性反思思潮,也有很大影响。张梦阳先生对此曾有过专门研究。

史密斯是位诚实、细心的观察家。读者在阅读中不难发现这一点。然而,诚实与信心并不意味着客观与准确。因为文化与时代的偏见与局限,对于任何一个个人都是无法超越的,尤其是一位生活在100年以前的基督教传教士。西方文化固有的优越感,基督教偏见,都不可避免地影响着史密斯在中国的生活经验和他对中国人与中国文化的印象与见解。基督教普世精神、西方中心主义,构成史密斯观察与叙述中国的既定视野。中国人的性格形象映在异域文化背景上,是否会变得模糊甚至扭曲呢?辜鸿铭说”要懂得真正的中国人和中国文明,那个人必须是深沉的、博大的和淳朴的”,”比如那个可敬的阿瑟。史密斯先生,他曾著过一本关于中国人特性的书,但他却不了解真正的中国人,因为作为一个美国人,他不够深沉。。”(《春秋大义》”序言”)

美国传教士眼里的中国人的形象,并不具有权威性。它是一面镜子,有些部分甚至可能成为哈哈镜,然而,问题是,一个美国人不能了解真正的中国人,一个中国人就能了解中国人吗?盲目的自尊与脆弱的自卑,怀念与希望,不断被提醒的挫折感与被误导的自鸣得意,我们能真正地认识我们自己吗?《中国人的性格》已经出版整整l00年了。一本有影响的著作成为一个世纪的话题,谁也绕不开它,即使沉默也是一种反应,辜鸿铭在论著与演说中弘扬”中国人的精神”,史密斯的书是他潜在的对话者,回答、解释或反驳,都离不开这个前提。林语堂的《吾国吾民》,其中颇费苦心的描述与小心翼翼的评价,无不让人感到《中国人的性格》的影响。《中国人的性格》已成为一种照临或逼视中国民族性格话语的目光,所有相关叙述,都无法回避。

我们不能盲信史密斯的观察与叙述都是事实,但也不必怀疑其中有事实有道理。读者们可以根据自己的阅读来判断。了解自己既需要反思也需要外观。异域文化的目光是我们理解自己的镜子。临照这面镜子需要坦诚、勇气与明辨的理性。鲁迅先生一直希望有人翻译这本书,在他逝世前14天发表的《”立此存照”(三)》中,先生还提到:”我至今还在希望有人翻译出斯密斯的《支那人气质》来。看了这些,而自省,分析,明白哪几点说的对,变革,挣扎,自做工夫,却不求别人的原谅和称赞,来证明究竟怎样的是中国人。

明恩溥观察到了中国文化的二十五种特征,他的这本书也包含了这二十五章,每个章的标题都是描述了一个特征,最后两章描述了宗教和社会。

第一章 保全面子

第二章 节俭持家

第三章 勤劳刻苦

第四章 讲究礼貌

第五章 漠视时间

第六章 漠视精确

第七章 易于误解

第八章 拐弯抹角

第九章 顺而不从

第十章 思绪含混

第十一章 不紧不慢

第十二章 轻视外族

第十三章 缺乏公心

第十四章 因循守旧

第十五章 随遇而安

第十六章 顽强生存

第十七章 能忍且韧

第十八章 知足常乐

第十九章 孝悌为先

第二十章 仁爱之心

第二十一章 缺乏同情

第二十二章 社会风波

第二十三章 诛连守法

第二十四章 相互猜疑

第二十五章 缺乏诚信

第二十六章 多元信仰

第二十七章 中国的现实与时务

明恩溥(Arthur Henderson Smith 1845—1932) 又作明恩普,阿瑟·亨德森·史密斯,美国人,基督教公理会来华传教士。1872年来华,最初在天津,1877年到鲁西北赈灾传教,在恩县庞庄建立其第一个教会,先后在此建立起小学、中学和医院,同时兼任上海《字林西报》通讯员。1905年辞去宣教之职。在明恩溥等人推动之下,1908年,美国正式宣布退还“庚子赔款”的半数,计1160余万美元给中国。第一次世界大战爆发后,明恩溥返回美国。

作为一个美国传教士,明恩溥深入天津、山东等地了解中国民众的生存状况,熟悉中国的国情,因而他知道如何以恰当的方式影响中国的未来。1906年,当他向美国总统西奥多·罗斯福建议,将清王朝支付给美国的“庚子赔款”用来在中国兴学、资助中国学生到美国留学时,他大概已经意识到了实施这一计划所能具备的历史意义。清华留美预备学校(后改名为清华大学)的成立,为中国留学生赴美打开了大门,一批又一批年轻学子从封闭的国度走向世界,他们中间涌现出众多优秀人才,归国后成为不同领域的精英。