漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

Geschichte

Geschichte

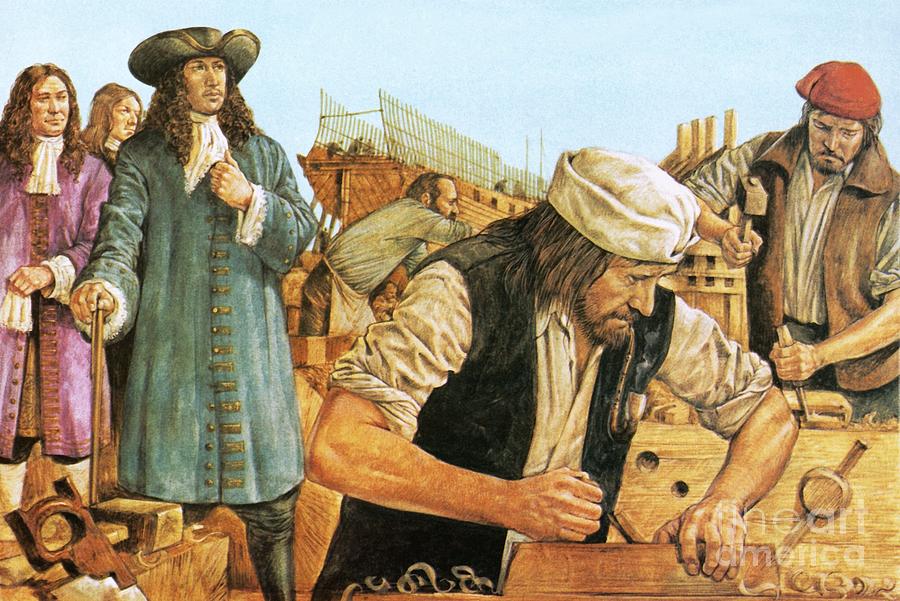

Peter the Great at Deptford in 1698

Peter the Great's trips to Europe

All researchers of the history of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the first Russian state public museum, the Kunstkamera, unanimously bond the idea of the establishment of these oldest Russian scientific institutions with the experience which Peter I gained during his trips to Europe.

Peter the Great was the first Russian Tsar to visit European countries. His first long trip to Europe took place in 1697–1698, within the frame of his so-called “Grand Embassy,” while the second one occurred twenty years later, in 1716–1717.

In between these diplomatic missions, Peter visited a number of cities in North Germany and Denmark in 1711-1713, during the military campaign of the Great Northern War.

Peter tried to stay incognito during the Grand Embassy and took part in it as a Peter Mikhailov, uriadnik (approximately corresponds to the modern military rank of “sergeant”) of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, although his recognizable appearance was hard to disguise. A special wax seal, which the Tsar was setting on each of his letters during his travel, had the inscription: “I am a pupil looking for mentors.”

He delegated the mission of important diplomatic negotiations with European monarchs to three “grand plenipotentiary ambassadors:” Franz Lefort, Fyodor Golovin, and Prokopy Voznitsyn, but de-facto, Peter himself quite frequently participated in negotiations with foreign sovereigns. He believed that this was an easier way for him to get acquainted with everyday life of European citizens, master different crafts, and, among other things, attend private collections of curiosities and scientific cabinets. Together with the Embassy, Peter the Great visited a number of cities in Livonia, Kurland, Prussia, Saxony, Holland, England, and Austria.

During his second travel to Europe in 1716–1717, Peter visited Danzig, Hamburg, Pyrmont, Mecklenburg, Rostock, Copenhagen, Bremen, Amersfoort, Utrecht, Amsterdam, Saardam, Hague, Leiden, Rotterdam, and Paris.

During these journeys Peter was always, whenever possible, meeting with European scholars, visiting private collections and galleries, and natural history cabinets. He used the opportunities of such meetings to invite all sorts of specialists, including academics, to come to work in Russia. Peter was personally and through his envoys establishing connections with book publishers in Holland and Germany; he organized purchases of a number of collections for the Apothecary Prikaz and, later on, for the Kunstkamera; studied anatomy and other sciences. Participants of the Grand Embassy also visited other cities and countries, where, upon Peter’s instructions, they were meeting with academics and publishers, and touring private museums and collections.

Indeed, from the documents, memoirs, and the chronicle of the Grand Embassy (“Journal of Daily Records”) it is known that in all cities visited by Peter the Great, he had a great interest in touring private museums and collections, part of which belonged to royal courts of Europe, and partly to scientists and owners of major trade companies (e.g., Dutch East India Company). It is known that only in Holland, a country which had produced the strongest impression on Peter, in the end of the 17th century, there were several tens of private museums and collections.

A far from complete list of private collections and museums visited by Peter the Great during his travel to European countries in 1697–1698 looks as follows:

– Collection of East-Indian and antique rarities, ship models and machines belonging to Nicolaes Witsen, Mayor of Amsterdam, Administrator of the Dutch East-Indian Company and a scholar

– Collection of antiquities “including coins, medals, and various minerals” of Peter Nicolaes Kalf in Saardam

– Anatomical and zoological museum of the professor of anatomy and botany in Amsterdam, Frederick Ruysch

– Amsterdam Botanical Garden with greenhouses and a museum with samples of the aquatic fauna from the overseas possessions of Holland (accompanied by Fr. Ruysch)

– East-Indian Yard in Amsterdam, where in the company’s buildings collections of Chinese and East-Indian weapons, Chinese paintings and maps were exposed, and a number of rooms were decorated with rare plants

– Home museum of merchant Jacob de Wilde, who had a valuable collection of antiquities: bronzes, carved stones, coins

– Cabinet of Nicolas Chevalier in Utrecht (Later on, in 1721, J. Schumacher acquired from the heirs a part of this collection for the Kunstkamera);

– Peter I visited A. Van Leeuwenhoek, naturalist and founding father of scientific microscopy, and scrutinized his cabinet with the collections

– Botanic Garden and Anatomical Theatre of Leiden University

– Museum of the London Royal Society and Mint collections in the Tower

– Ashmolean Museum in Oxford

– Royal Kunstkamera in Dresden

– Armory, Kunstkamera, and Art Gallery in Vienna, at the court of Emperor Leopold I.

Peter had visited many of these collections and Kunstkameras during his second long journey to Europe in 1716–1717.

In some cases we know the details of Peter’s visits for exploring the collections, which clearly point up his interests. For example, there is a detailed description of his daily visits to the Kunstkamera in Dresden during his short stay in this city in June 1698. Peter arrived in Dresden in the late afternoon and, after dinner, asked to show him the famous Kunstkamera. Vice-regent Furstenberg took him there at one o’clock in the morning, and the Tsar was scrutinizing the collections till the morning; he was particularly meticulous in familiarizing with mathematical instruments and handicraftsman's implements. Next day, after the lunch and visit to Kurfürst’s mother, he visited the Kunstkamera again. On the third day, after watching military exercises, Peter visited the mould yard and, once again, the Kunstkamera. One more time Peter had visited the Dresden Kunstkamera during his stay in Dresden in September 1711[2]. In the course of his third visit to Dresden in November 1712, Peter stayed in the house of the court’s jeweler Johann Melchior Dinglinger. In the collection of “Grünes Gewölbe” (former Kunstkamera), there is a small enamel portrait of the Russian Tsar made by the jeweler’s brother, Georg Friedrich Dinglinger, in remembrance of these visits to Dresden.

In1717, when Peter I got the word that in the collection of Dutch collector Goswin Uylenbroek a Roman sarcophagus is treasured, he took a fancy to see it. The owner made a record of the details of this visit: “When Tsar Peter the Great did me the honor to see my cabinet, and the thing had to be placed into a dark storeroom because of its huge size, His Highness asked for two candelabrums with candles and kneed down to look thoroughly around the whole sarcophagus and each figure on it in all details”.

Pius V., bürgerlicher Name Antonio Michele Ghislieri OP (* 17. Januar 1504 in Bosco Marengo bei Alessandria; † 1. Mai 1572 in Rom), war von seiner Wahl am 7. Januar 1566 bis zu seinem Tod Papst der katholischen Kirche. Er wurde 1712 heiliggesprochen.

教宗圣人庇护五世(英语:Pope Saint Pius V;拉丁语:Sanctus Papa Pius V,1504年1月17日-1572年5月1日),原名Antonio Ghislieri(1518年起称Michele Ghislieri),从1566年1月7日起,至1572年5月1日在位。在罗马天主教中,他被尊奉为圣人。[2]

庇护五世以他在脱利腾会议中的举措,反宗教改革以及整顿天主教会内部的秩序而闻名。其任内,宣布托马斯·阿奎那为教会圣师之一。[3][4]

在外交方面,因伊丽莎白一世对英国公教会所施行的迫害与裂教行为,庇护五世将其逐出教门。庇护五世也组织了神圣同盟,以抗击奥斯曼帝国对欧洲的进攻。其后,神圣同盟于勒班陀战役中击溃了奥斯曼海军,令奥斯曼帝国从此失去在地中海的海上霸权。庇护五世将此次胜利归功于圣母玛利亚的代祷与协助,并下令将进教之佑一祷词列入圣母祷文,并钦定10月7日为圣母玫瑰节。[5]

Pythagoras von Samos (griechisch Πυθαγόρας; * um 570 v. Chr. auf Samos; † nach 510 v. Chr. in Metapont in der Basilicata) war ein antiker griechischer Philosoph (Vorsokratiker) und Gründer einer einflussreichen religiös-philosophischen Bewegung. Als Vierzigjähriger verließ er seine griechische Heimat und wanderte nach Süditalien aus. Dort gründete er eine Schule und betätigte sich auch politisch. Trotz intensiver Bemühungen der Forschung gehört er noch heute zu den rätselhaftesten Persönlichkeiten der Antike. Manche Historiker zählen ihn zu den Pionieren der beginnenden griechischen Philosophie, Mathematik und Naturwissenschaft, andere meinen, er sei vorwiegend oder ausschließlich ein Verkünder religiöser Lehren gewesen. Möglicherweise konnte er diese Bereiche verbinden. Die nach ihm benannten Pythagoreer blieben auch nach seinem Tod kulturgeschichtlich bedeutsam.

毕达哥拉斯(希腊语:Πυθαγόρας,前570年—前495年)是一名古希腊哲学家、数学家和音乐理论家,毕达哥拉斯主义的创立者。他认为数学可以解释世界上的一切事物,对数字痴迷到几近崇拜;同时认为一切真理都可以用比例、平方及直角三角形去反映和证实:譬如主张平方数"100"意味“公正”。毕达哥拉斯主义描述毕达哥拉斯和追随者所持的秘教和形而上学的思想学说的术语,他们都深受数学所影响,如数秘术和数字神秘主义的生命灵数及彩虹数字学。

Abstrakte Kunst

Abstrakte Kunst

École de Paris

École de Paris

Moderne École de Paris

Moderne École de Paris

Geschichte

Geschichte

M 1500 - 2000 nach Christus

M 1500 - 2000 nach Christus

Kubismus

Kubismus

Pablo Ruiz Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (* 25. Oktober 1881 in Málaga, Spanien; † 8. April 1973 in Mougins, Frankreich)[1] war ein spanischer Maler, Grafiker und Bildhauer. Sein umfangreiches Gesamtwerk umfasst Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Grafiken, Collagen, Plastiken und Keramiken, deren Gesamtzahl auf 50.000 geschätzt wird. Es ist geprägt durch eine große Vielfalt künstlerischer Ausdrucksformen und Techniken. Die Werke aus seiner Blauen und Rosa Periode und die Begründung des Kubismus zusammen mit Georges Braque bilden den Beginn seiner außerordentlichen Künstlerlaufbahn.

Zu den bekanntesten Werken Picassos gehört das Gemälde Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Es avancierte zum Schlüsselbild der Klassischen Moderne.[2] Mit Ausnahme des monumentalen Gemäldes Guernica (1937), einer künstlerischen Umsetzung der Schrecken des Spanischen Bürgerkriegs, hat kein anderes Kunstwerk des 20. Jahrhunderts die Forschung so herausgefordert wie die Demoiselles.[2] Das Motiv der Taube auf dem Plakat, das er im Jahr 1949 für den Pariser Weltfriedenskongress entwarf, wurde weltweit zum Friedenssymbol.

Umfassende Sammlungen von Picasso werden in Museen in Paris, Barcelona und Madrid gezeigt. Er ist mit Werken in vielen bedeutenden Kunstmuseen der Welt, die die Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts ausstellen, prominent vertreten. Das Museu Picasso in Barcelona und das Musée Picasso in Antibes entstanden bereits zu Lebzeiten.

巴勃罗·鲁伊斯·毕加索(西班牙语:Pablo Ruiz Picasso,1881年10月25日—1973年4月8日),西班牙著名的艺术家、画家、雕塑家、版画家、舞台设计师、作家和前法国共产党党员,出名于法国,和乔治·布拉克同为立体主义的创始者,是20世纪现代艺术的主要代表人物之一,遗作逾两万件。毕加索、马塞尔·杜象和亨利·马蒂斯是三位在二十世纪初期开始造型艺术革命性发展的艺术家,在绘画、雕塑、版画及陶瓷上都有显著的进展。在西班牙与萨尔瓦多·达利和胡安·米罗被称为西班牙后三大艺术家。

Bi Sheng (chinesisch 畢昇 / 毕昇, Pinyin Bì Shēng, W.-G. Pi Sheng; 972; † 1051), ein Mann niedriger Abstammung, erfand zwischen 1041 und 1048 im Kaiserreich China eine Methode des Drucks mit beweglichen Lettern. Näheres über sein Leben ist nicht aufgezeichnet.

Seine Erfindung wird detailliert von Shen Kuo in dessen Werk Mengxi Bitan (夢溪筆談; dt. „Pinselunterhaltungen am Traumbach“) beschrieben: Bi Sheng hatte für die einzelnen Schriftzeichen Druckstempel aus gebranntem Ton gefertigt, die er mit einer Mischung aus Wachs und Harz zum Druckstock einrichtete.

- Um zu drucken, setzte er einen Eisenrahmen auf eine Eisenplatte und ordnete darin die Stempel an. War der Rahmen voll, dann ergab dies einen Druckstock, den er dann erhitzte, bis die Paste [an der Rückseite der Lettern] zu schmelzen begann. Mit einem Brett, das er an die Vorderseite drückte, ebnete er die Oberfläche des Druckstocks damit sie glatt wurde wie geschliffen.

- Von jedem Schriftzeichen hatte er mehrere Stücke, und für häufig vorkommende zwanzig und mehr, um für Wiederholungen auf einer Seite gerüstet zu sein. Nicht benutzte Schriftzeichen etikettierte er und bewahrte sie in hölzernen Schachteln auf. (Lit. Tsien)

Um die Zeichen erneut zu verwenden, wurde die Eisenplatte neuerlich erhitzt, bis die schmelzende Paste die Stempel wieder freigab. Für größere Druckflächen waren Bi Shengs Keramiklettern aber zu empfindlich (Lit. Sohn).

Wang Zhen (1260–1330) nutzte deshalb später bewegliche Lettern aus Holz, dennoch setzte sich der Druck mit beweglichen Lettern in China bis zum Ausgang des 19. Jahrhunderts nicht durch. Sachbeweise für die praktische Nutzung von Bi Shengs Erfindung existieren nicht, die Erfindung geriet wieder in Vergessenheit.

Der Grund liegt wohl nahe: Die Tausenden chinesischer Schriftzeichen vereiteln das einfache und schnelle Zusammenstellen von Druckplatten auf diese Art.

Erst Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts druckten europäische Jesuiten-Missionare nach dem Prinzip des Johannes Gutenberg erstmals auf chinesischem Boden im Auftrag des Kaisers Kangxi Bücher mit beweglichen Lettern.

Der Mondkrater Bi Sheng ist seit 2010 nach ihm benannt.

Architektur

Architektur

Chinesische Architektur

Chinesische Architektur

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Geschichte

Geschichte

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

Urlaub und Reisen

Urlaub und Reisen

Der Tempel der Azurblauen Wolken (chinesisch 碧云寺 Biyun si, englisch Temple of Azure Clouds) ist ein buddhistisches Tempelkloster im östlichen Teil der Pekinger Westberge (Xīshān 西山) gerade außerhalb des Nordtores des Duftberg-Parks (Xiangshan Gongyuan 香山公园) im Bezirk Haidian, einem nordwestlichen Vorort von Peking, China, ca. 20 km vom Stadtzentrum entfernt. Er wurde im 14. Jahrhundert erbaut, im Jahr 1331 während der Yuan-Dynastie (1271-1368), und wurde 1748 erweitert.

Wissenschaft und Technik

Wissenschaft und Technik

Finanz

Finanz

Historische Münzen, Banknoten

Historische Münzen, Banknoten

Religion

Religion

Sachsen-Anhalt

Sachsen-Anhalt

Kunst

Kunst

Toscana

Toscana